As we celebrate International Women’s Day each year, it has become a tradition for me to delve into the dynamic realm of ecofeminism, sharing insights, theories, activities, and projects that intersect environmental advocacy with feminist principles. While my focus in 2022 was captivated by the primal elements of fire, exploring the resilient beauty of plants like fireweed through my artistic endeavors (see e.g. An Ash Tree in Os – a feminist science fiction story about grief and loss – got published), the year 2025 marks a shift in my thematic explorations, drawing me irresistibly back to the elemental theme of water (and water lilies, snakes, and water spirits).

1. The Book Project and Ecomythology: Restor(y)ing the Baltic Sea

This year, my academic and creative focus is predominantly centered on significant aquatic bodies like the North and Baltic Seas. Last year, Vitalija, Evelin, Heide and I have dedicated myself to drafting an abstract for a forthcoming book chapter, as well as a manifesto-like document that articulates my evolving thoughts on ecofeminism and hydrofeminism. Looking ahead to 2026, we are particularly thrilled about our involvement in an upcoming publication titled “Brackish Blue Humanities and Environmental Art: Thinking with the Baltic Sea.”

In collaboration with co-authors Vitalija Povilaityte-Petri, Heide Maria Baden, and Evelin Grauen, we will delve into “Flowing with Eglė’s Ecomythology: Restor(y)ing the Baltic Sea,” which is another creative outcome of our collaborative Flowing with Eglė – Project.

2. The Antwerp Workshop: A Multifaceted Approach to Hydrofeminism

During the 2025 International Design Workshop week at the University of Antwerp, I introduced hydrofeminist concepts to students across various disciplines. Our exploration included a session of forest bathing in Rivierenhof, Antwerp’s largest park, which served as a way to connect with the local water body, het Schijn, and perhaps to also heal with the wounded landscape. See my published academic essay on forest bathing as a creative practice of knowledge creation and healing with/through/in wounded landscapes.

Students engaged creatively with hydrofeminist ideas, including a notable project where they cooked biopolymers using river water. This experiment was not only a practical application of sustainable practices but also tied into the creation of a mythic being connected with het Schijn. In this same team, the students made a water lily with biopolymers. The water lily is a plant with deep (hydro)feminist significance. See The water lily, the serpent and the nøkk, an ecofeminist trinity?.

A key part of the workshop was watching and discussing the film ‘Beasts of the Southern Wild,’ based in the Bathtub, a fictional place in Louisiana, which provided a rich basis for conversation about the interplay between folklore, myth, and ecological awareness in contemporary media. It is about the fear for floodings, about vague boundaries, and control.

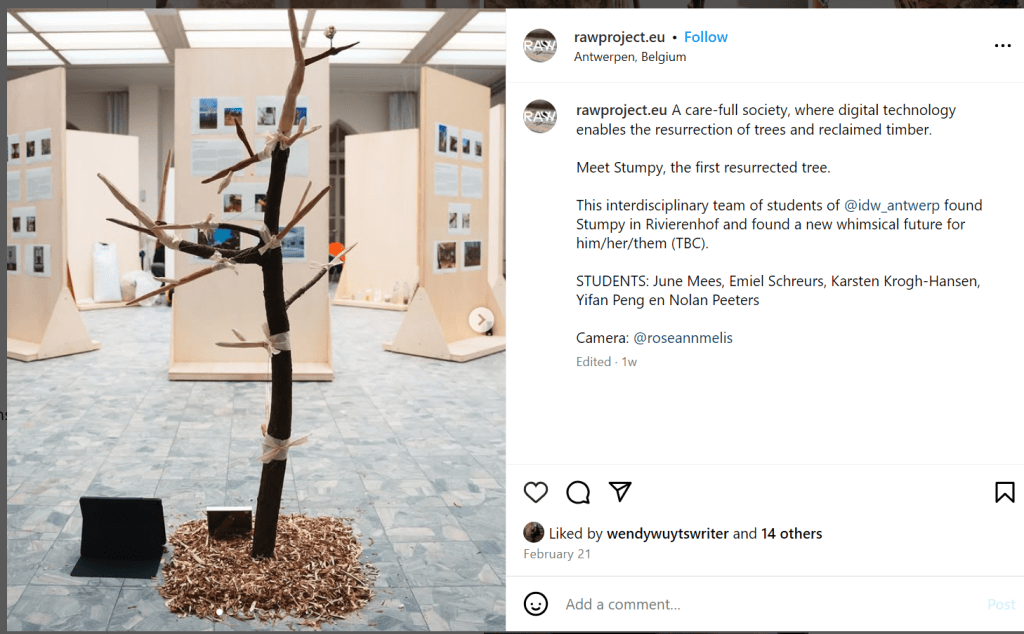

Some students chose to explore themes around ‘Stumpy,’ a tree being entity I had previously discussed in A Final Hydrofeminist Salute: Bidding Farewell to Stumpy, Washington’s Cherished Cherry Tree Victim of Climate Change Adaptation.

3. Stumpy in Washington DC and the Academic Article Under Review

My engagement with Stumpy extended beyond student projects to a blog (A Final Hydrofeminist Salute: Bidding Farewell to Stumpy, Washington’s Cherished Cherry Tree Victim of Climate Change Adaptation), but also to an academic article currently under review, which challenges traditional architectural and engineering boundaries through a hydrofeminist lens. This article discusses the significance of soft versus hard boundaries in urban and natural environments, inspired by my observations in Washington DC.

In this academic essay I also refer to the entanglements around het Schijn. During a second visit to Rivierenhof, Antwerp’s largest park, I was eager to revisit the infrastructure surrounding het Schijn, particularly to discuss the river’s repeated relocations primarily for port development. However, to my surprise, access was restricted due to the commencement of the Oosterweel connection project. This massive infrastructure initiative aims to complete the Antwerp Ring Road, significantly altering the landscape.

Witnessing the changes, the area appeared more wounded than before—a metaphor for the disruptions that often accompany such large-scale urban developments. This visit starkly highlighted the tension between development and ecological preservation, reinforcing the need for a hydrofeminist perspective in urban planning and development projects.

4. Skopje: A City Through a Hydrofeminist Lens

My explorations of Skopje, a city marked by its complex history and the controversial Skopje 2014 project, offered a unique opportunity to view urban renewal through a hydrofeminist lens. I was there on holidays, but I could not ignore what I saw through my hydrofeminist goggles. The Skopje 2014 project, characterized by the installation of numerous neoclassical buildings and white statues, ostensibly aimed to revive and honor ancient Macedonian heritage but has been criticized for its selective memory and aesthetic choices. This ‘antiquisition’—the artificial imposition of a glorified past—struck me deeply, prompting a reflection on what narratives are amplified and which ones are silenced.

In Skopje, the stark white of the new monuments stands in contrast to the lived reality of the city’s diverse and dynamic population. The project’s emphasis on a sanitized, heroic past overlooks the rich tapestry of stories that include, but are not limited to, the experiences of women, thus echoing a binary thinking between what is considered pure and impure. This approach to urban design not only divides physical spaces but also cultural narratives, presenting a challenge to the inclusive and interconnected perspective advocated by hydrofeminism.

As I navigated the city, the visible traces of this ‘cleansing’ seemed almost to erase the nuanced histories of its inhabitants, particularly women, whose contributions and experiences are seldom memorialized in such grandiose projects. However, despite these challenges, Skopje remains a living, breathing city with porosity that belies its seemingly rigid facades. The city’s nickname, “The City of Seven Gates,” metaphorically suggests openness and passage, qualities that are essential to understanding its true spirit.

Looking forward to Skopje’s designation as the cultural capital in 2028, I am curious about the potential uncovering of hidden layers of history and stories. This upcoming spotlight provides an invaluable chance to redefine and rediscover Skopje’s identity—not through the lens of past empires or political agendas but through the diverse narratives that make it truly vibrant. A hydrofeminist approach encourages us to look beyond the surface, to the interconnections and flows that define not just rivers and lakes, but human communities and ecosystems—a perspective that can hopefully guide the city towards a more inclusive and ecologically integrated future.

5. Istanbul, Medusa, and the Book by Veronica Strange

My travels also took me to Istanbul, where the symbolic presence of a Medusa statue in the cisterns reminded me of Veronica Strange’s book connecting snakes, water, and women, which I had read the previous summer. This connection further deepened my understanding of the intricate ties between mythology, gender, and environmental narratives, as you can read in this blog: The water lily, the serpent and the nøkk, an ecofeminist trinity?

6. “Het Lied van Sulina”: A Hydrofeminist Flemish Book that should be translated

This year witnessed the publication of maybe a first hydrofeminist book in the Flemish landscape… and it was not written by undersigned. No.

“Het Lied van Sulina,” a compelling novel by Anneleen Van Offel, represents a significant exploration within the hydrofeminist literary landscape. This narrative elegantly weaves together the elements of water, land, and the profound connections between mother and child, blurring the traditional boundaries that often define and constrain these relationships. Van Offel crafts a story that flows like a river—starting from the mysterious depths of the Black Forest, tracing the course of the Danube, and culminating at its expansive delta in the Black Sea. The journey through these waterways serves as a metaphor for the interconnectedness of life, echoing the central themes of hydrofeminism.

Van Offel’s narrative technique is particularly resonant for those immersed in hydrofeminism, as she challenges readers to navigate the fluid spaces between fiction and autobiography, myth and reality. The novel’s journey is not just geographical but also deeply introspective, exploring the ethereal dreams and mythic underpinnings that connect us to our environment. “Het Lied van Sulina” dissolves the rigid separations between body and environment, right and wrong, highlighting the permeability and transient nature of these constructs.

The book’s impact is further deepened by its subtle engagement with the hydrofeminist writings of Astrida Neimanis and the mythological research of Marija Gimbutas, echoing themes of ancient femininity and ecological consciousness. This synthesis of ideas invites readers to see the scientific and mythical not as opposing forces but as complementary strands of a single narrative tapestry. Van Offel’s work is a testament to the power of hydrofeminist thought, offering a narrative that is as enriching as it is enlightening, ideal for those who seek to explore the depths of both human and ecological interrelations.

6. Mjøsa: The Heartbeat of Gjøvik and a Source of Inspiration

Lake Mjøsa, the largest lake in Norway, has been a constant presence in my life since I made my home in Gjøvik nearly four years ago. I wrote already a short flash fiction story: Flash fiction: Marta + Mjøsa

This body of water not only defines the landscape but also deeply influences the cultural and ecological fabric of the region. Mjøsa, with its fluctuating rhythms, mirrors the fluidity and resilience that are central to hydrofeminist thought. Throughout the seasons, whether witnessing the serene ice cover in winter or the aquatic life in summer, Mjøsa continuously offers new lenses through which to view our interactions with natural water systems. It is here by its shores that I feel most connected to the themes of ecomythology and ecofeminism, drawing inspiration for my writings, art, and reflections. One of these months I will write a love letter to Mjøsa.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.