At the end of October, I left Europe for 3–4 weeks in Mexico, more specifically the Maya region, which is partly situated on the Yucatán Peninsula. Via GetYourGuide, I booked a tour to visit cenotes, learn more about the spirited world, and support eco-tourism and Indigenous guardians. Apparently, I was the only one interested in that, and after some back-and-forth with the guide over whatsapp, it was decided that I would join a more mainstream tour combining two cenotes and the old Maya site of Uxmal. When we arrived at the first cenote, the other tourists hurried to the changing rooms, but the guide remembered my interest in nature connection and the spirited world and told me about the Aluxes.

Aluxes, guardians of the cenotes

Aluxes (pronounced “ah-loo-shays”) are mischievous, gnome-like nature spirits from Mayan folklore, acting as guardians of the jungle, crops, caves and sacred sites, protecting them from harm but playing tricks if disrespected, like the tree spirits of Okinawa in Japan. Often appearing as tiny beings with wide eyes, they can be invisible but manifest as small figures in traditional Mayan clothing, sometimes blending animal features, and require offerings or permission to interact with their domains.

Protection and permission

In the Maya world, cenotes were considered sacred portals to Xibalba, the underworld. If you know your geology, you know that cenotes appeared after the large meteor hit Yucatán—the meteor that led to the extinction of the dinosaurs. As the soil was mostly limestone, it created many holes that later filled with water. There are thousands of cenotes, some of them still undiscovered, many managed by Maya communities. As the primary source of fresh water in the region (there are no large rivers there, if I studied the map correctly), cenotes were crucial for survival. This led to their use as sites for sacred rituals, including offerings of pottery, jade, and even human sacrifices, to appease gods such as Chaac, the god of rain.

Today, you have to ask the Aluxes’ permission before entering a cave or cenote. As I had a wound on my ankle (thanks to the mosquitoes), the guide told me to ask the Aluxes for permission and to ask them not to send biting fish my way—fish that love dead skin cells. I did, and I was not attacked by any monsters.

I start to see them everywhere

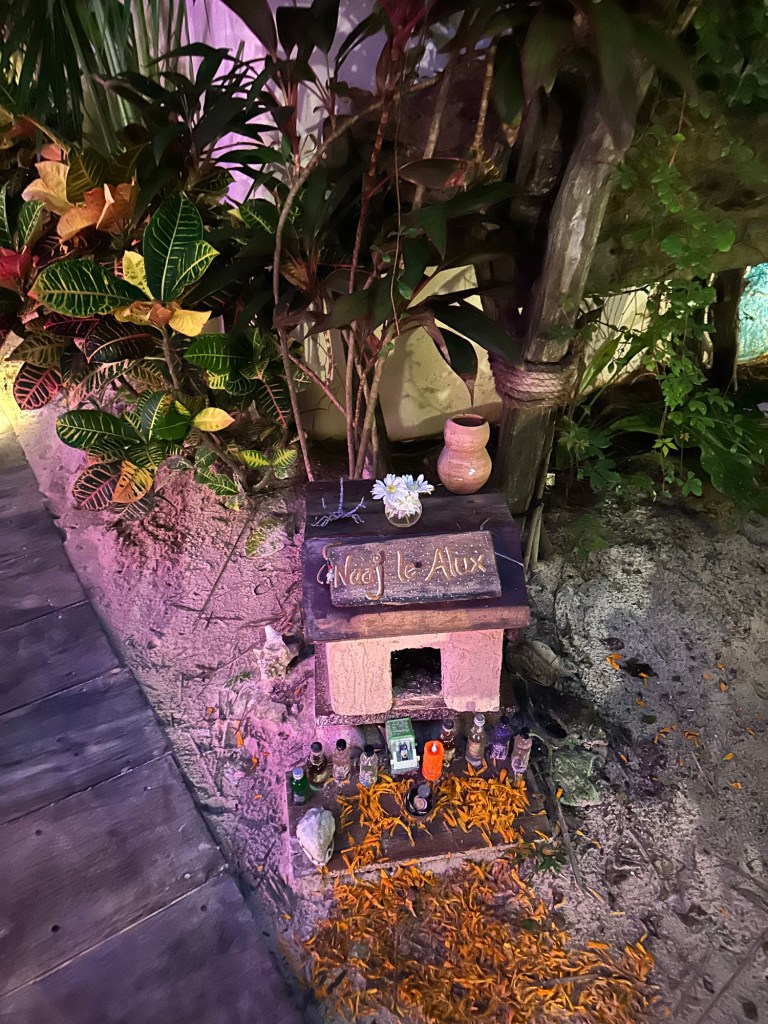

When I gazed out of the bus window, I saw some mini temples close to the construction of a bridge, or next to a busier road. I could not take pictures of these. In my eco-tourist hotel in Tulum, I also saw a little casita with offerings, and the hotel manager indeed told me it was for the Aluxes. The Alux houses (casitas) are often small clay houses built for them, usually with offerings, to gain their favor and secure their protection, as seen in construction projects such as the Cancún–Nizuc bridge. Traditional offerings include sakab (a sacred corn drink), sweets, tobacco, or food, with rituals performed to ask for blessings and permission to enter sacred areas. The way they build these offerings reminded me of small spirit houses in Thailand. In the new museum in Jaguar Park in Tulum, there was also an Alux statue where you could offer some coins.

Apparently, during the construction of the highly contested Maya Train project, Aluxes were also spotted. AMLO, who was president at the time, even tweeted about it.

According to Lirien Thornveil, “The belief in these spirits (pronounced “ah-loo-shes”) dates back to the Classical Maya period (250–900 CE), though some suggest the tradition is even older. In Mayan mythology, these beings were created from clay, corn, and sacred elements by the gods themselves, much like humans. However, unlike people, these spirits were given eternal youth, remaining childlike in size and temperament. Their main duty was to serve as guardians of nature, ensuring that forests, fields, and sacred sites were respected. Mayan farmers, in particular, held the Aluxes in high regard, believing they could bless their crops with fertility—so long as they were treated well.” (Source: https://enchanted-chronicles.com/aluxes-mayan-guardians-tricksters/ )

But let’s not romanticize maya culture too much

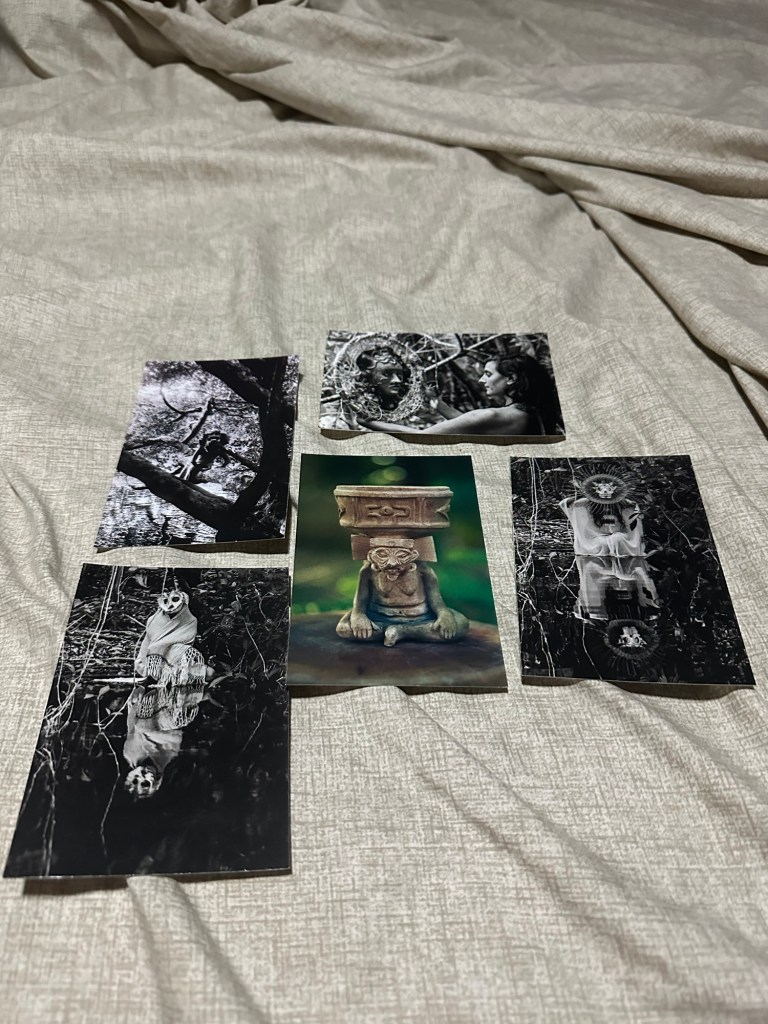

Although I love all the stories across cultures about tree spirits or other guardians like the fjosnissen in Norway, or as aforementioned the tree trolls in Okinawa or the tree spirits in Thailand, especially those with pre-Christian elements, there might be a risk of romanticizing pre-Christian cultures too much. During my tour in Uxmal, I was reminded of the hierarchical and violent aspects of Maya culture and traditions. It was a culture with slavery and other systems of exploitation. When I arrived at a jungle cabin in an eco-tourist resort in Bacalar, my favorite place on the peninsula, I found some artwork of Aluxes…

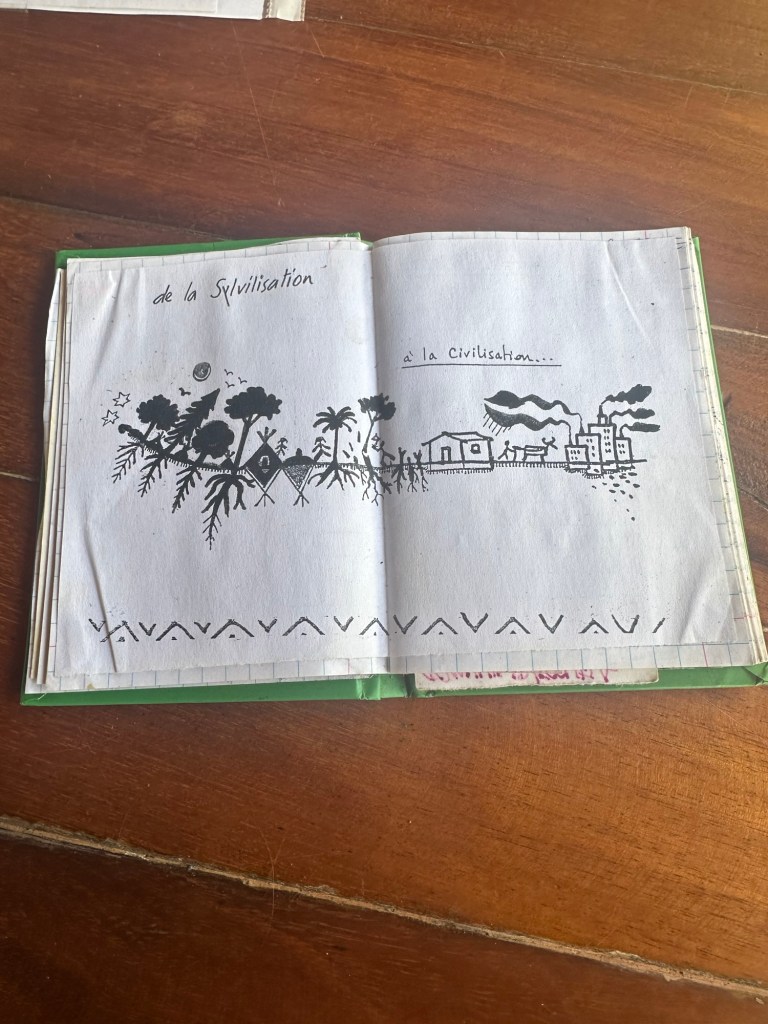

… I also met some people who lived very simply and were working on deep ecology ideas. One of them was a Belgian woman of maybe 80-90 years old who had lived in the jungle for decades. When I asked her, in a mix of French, Spanish, and English, her opinion of Aluxes, she did not know them. She was interested in a world before the exploitative Maya worldview and agricultural practices began to change the forest and the world in that place. Although some people say that the Maya were closer to nature than we are today (or than many of us are), we should not assume they were perfect examples of nature connection.

However, rituals and offerings to the land matter

That said, I think it is charming when farmers and other land guardians perform rituals and ceremonies, once a day, once a week, once a season, or once a year, for the spirits of the land. It shows that they believe in wonder and magic, and that they care for and respect the land and all beings, especially the invisible friends and helpers.

Do you know examples of similar tree spirits or other land guardians in your own culture? Let me know in the comments, and which ceremonies, practices and rituals you observed.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.