During the 2025 Summer Symposium in Finland, our study circle on transformative learning practices with the more-than-human world at the Nordic Summer University organized a fishbowl discussion—a participatory format where a smaller group (the “inner circle” or “fishbowl”) engages in focused conversation while a larger group (the “outer circle”) observes and later provides feedback.

For me, it was important to engage with the country where we hosted our event, as well as with the ideas and even the imaginary creatures that shape its cultural landscape, grounding our symposium in its local context – even if we had only a small timeslot of 1,5 hour (which is never enough to get to know a country, a place and the relations and stories in depth). The words we placed in the fishbowl were: Moomins, queer ecology, decolonizing art practice, whiteness, Finland, and Sápmi.

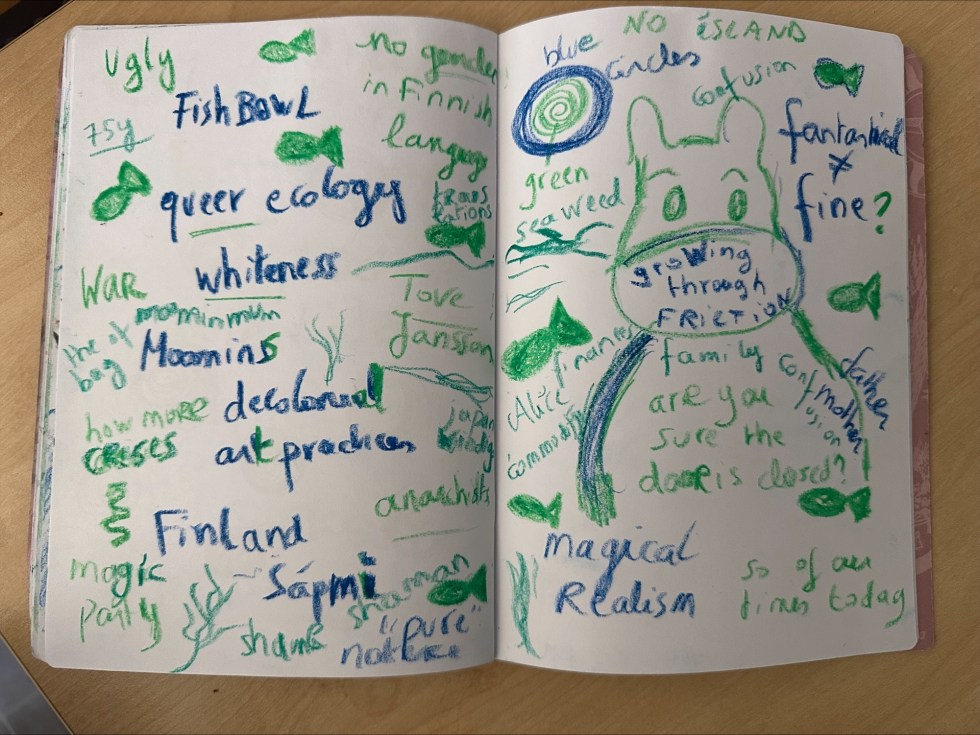

Although I did not participate directly in the discussion, I served as the facilitator, processing the dialogue by drawing and writing down the words and thoughts that resonated with me. This short blog post cannot capture the full richness of the 1.5-hour session, but it offers a few breadcrumbs for further exploration.

The fishbowl method

Before the session, I arranged two circles with different chairs: an inner circle with green chairs and an outer circle with blue chairs. I invited three participants from Finland, one of the coordinators of another study circle with whom we collaborated throughout the symposium (focused on decolonizing the Anthropocene through art practices), and a forest bath guide along with her teenage daughter. I was particularly glad that the teenage daughter joined, as her presence added an element of intergenerational learning to the discussion.

In a fishbowl discussion, participants are divided into two groups: the inner circle (typically 3–7 people) and the outer circle. The inner circle sits in a visible area, usually arranged in a circle or semi-circle, resembling a fishbowl. This group engages in a focused conversation on a specific topic, prompted by a facilitator or a guiding question. The outer circle observes the discussion, often taking notes and reflecting on the process without intervening.

However, I use a variation of this format. In my version, one seat in the inner circle is intentionally left open, allowing members of the outer circle to step into the discussion. Whenever someone from the outer circle takes the open seat, a participant from the inner circle must step out, creating a dynamic and fluid exchange.

Introduction before the fishbowl

One of the creatures you can hardly ignore upon arriving in Finland are the Moomins. Naturally, we placed them in the fishbowl as one of our discussion elements. I was unsure how familiar the participants of the study circles were with the Moomins, so I prepared a short introduction. To set the stage, I shared a video and showed the first two chapters—about ten minutes in total—giving everyone a glimpse into the whimsical yet thought-provoking world of these beloved characters.

The Finnish participants who started the the fishbowl offered some observations about language, noting that certain ideas might be lost in translation. In Finnish, there is no grammatical gender, which sparked an engaging conversation about how language shapes thought and cultural understanding.

Queerness in Moominvalley

It is now widely recognized that Tove Jansson explored various aspects of queer life and experience in her work, including themes of “being different,” same-sex love and affection, and gender fluidity. One of the participants in our session had previously attended talks on Moomins and queerness and shared with us a YouTube link to a panel discussion on the topic.

In this panel, literary scholar Ásta Kristín Benediktsdóttir discusses queerness in Moominvalley and other literary spaces created by Tove Jansson, alongside translator and writer Þórdís Gísladóttir, teacher Hildur Ýr Ísberg, and queer activist Hilmar Hildar Magnúsarson. Together, they explore questions such as: How is queerness translated into Icelandic? And how does it resonate with modern readers of different ages?

The Moomins, Commodification, and the Return of Magical Realism

Tove Jansson—an artist whose work often navigated the boundaries between the fantastical and the fine arts—became a focal point of our discussion. Different participants shared stories they had heard about Jansson, touching on her queerness, speculating whether she eventually grew tired of the Moomins, and reflecting on the commodification of her creations. This naturally expanded into a broader conversation about contemporary artists who, like Jansson, often have to take on other jobs to sustain their art practice, highlighting the ongoing tension between art and the market, creativity and capital.

These reflections tied closely to the overarching theme of our week-long symposium on the economy and what we can learn from the more-than-human world. Participants also noted how fine arts have historically been perceived as “superior” to the fantastical, yet today we are witnessing a resurgence of magical realism in Europe. One participant observed that she had heard about at least three exhibitions centered on magical realism this summer, wondering aloud whether times of crisis bring a greater need for ‘party’ and ‘magic’.

Moomins, whiteness and hyper racism

Some days later, one of the Finnish participants shared the news that Stinky (Haisuli) is Moomin character has been dropped from a major exhibition at Brooklyn Public Library in New York after one of the institution’s supporters raised concerns that the character might be perceived as racist.

It’s clear that the Moomins can prompt fascinating discussions about identity, coloniality, and cultural norms. In our fishbowl, we briefly touched on the theme of whiteness, one of our keywords along with Finland and Sápmi. The intention was to connect these themes with the Sámi people and the ideas around whiteness, purity, shame—and to reflect that while the Moomins appear “white,” that whiteness may not tie them to Sámi or Finnish identities or ideals.

Why this matters:

- The Moomins exist in a liminal space—they are iconic symbols of Finnish culture, yet they seem deliberately non-human, perhaps resisting easy alignment with categories like whiteness or indigeneity.

- This ambiguity became interesting—are they neutral, or do they carry an implicit representation of Finnish whiteness?

Please add links or your ideas how to link the whimsical world of the Moomins to real-world histories of whiteness, indigenous erasure, and cultural identity in Finland and Sápmi.

Beyond Cuteness: The Moomins as a Gateway to Deeper Conversations

Lastly, the participants also touched on the use of cuteness in relation to the Moomins, a quality that is also strongly present in Japanese culture. There is even a so-called Japanese version of the Moomins, which, as I understood, emphasizes commodification while erasing some of the original nuances.

Having lived in Japan, I understand what they meant by this “cuteness” and have also sensed the danger of sugarcoating stories—how cuteness can sometimes prevent people from engaging with deeper meanings. This is precisely why conversations like our fishbowl are so important: they allow us to use the Moomins not just as charming characters, but as entry points into more profound discussions. Such dialogues can pierce through the layers of sugarcoating and commodification—and even challenge how cuteness can sometimes be co-opted by extreme political agendas, including ecofascism.

For me, the real magic of transformative learning lies in these conversations—especially those that embrace tensions, dilemmas, and choices without clear answers. To borrow from the language of the Moomins, the door remains open for further learning. This means not romanticizing the Moomins, but rather staying curious about the diverse interpretations, associations, and even misuses of these characters—just as any creature or creation can, at times, be appropriated for purposes far from its original spirit. As one participant remarked: We cannot know what Tove Jansson might have thought about the entire Moomin renaissance and its commodification. We will never know… and perhaps, in this not knowing, there is a certain power.

Further (academic) reading:

Darwish, Maria. “Fascism, nature and communication: a Discursive-affective analysis of cuteness in ecofascist propaganda.” Feminist Media Studies 25.2 (2025): 443-463.

Johnson, Ida Moen. “Queer Species in Moominvalley: A Posthumanist Reading of Tove Jansson’s Moomin Books.” International Research in Children’s Literature 16.2 (2023): 184-197.

Kuokkanen, Rauna. “All I see is white: The colonial problem in Finland.” Finnishness, whiteness and coloniality. Helsinki University Press, 2022. 291-314.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.