As aforementioned, this spring and summer, we are combining the method of Writing (with) plants with the Flowing with Eglė – Project, where we create a new eco-myth. In this old myth, different human characters transform in trees, and we invite these trees as our guests in writing(with)plant sessions.

the HARVEST FROM OUR WRITING(WITH)ASH SESSION

A few days before Easter celebration on Sunday April 20th, and in the middle of the Jewish Passover, which began on Saturday, April 12, and ends after nightfall on Sunday, April 20, we invited the Ash Tree in our space. We had ten attendees, who called in from the USA, Canada, Lithuania, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Austria and France. The titles of the next subsections come straight from the words spoken by participants during this two-hour gathering. In this blog post, I weave together those reflections into a living proposal: Who is Ash in our emerging eco-mythology—and what could his story arc be in the myth we’re collectively dreaming into being?

the preparation

While preparing for this writing-with-Ash session, I was reminded of just how deeply I’ve worked with this tree. I’ve written several blog posts about specific ash trees—both real and mythological, like Yggdrasil (e.g. An Ash Tree in London’s Old Burial Ground; Norwegian Easter: time for ash and crime). One of my published short stories is even centered around an Ash Tree in Os.

Given the prominent role ash trees play in Norwegian mythology, this connection isn’t surprising. I’ve been drawn to Norwegian folklore since childhood. The ash tree, in particular, carries powerful symbolism: death and rebirth, and sacrifice in exchange for greater wisdom. In one of the old myths, Odin hung himself from Yggdrasil for nine days to gain profound knowledge—of the runes, of writing, of translating wisdom into new forms. This shift—from oral tradition to the written word—brought both gains and losses, and its impact still echoes today.

I mean, without his sacrifice, there would be no blog posts. No runes, no writing, no way to pass on stories beyond the flicker of firelight and the memory of a circle. Odin’s offering gave us the tools to record, reflect, and reimagine—and perhaps, through writing, to remember what we’ve forgotten. In that sense, every typed word owes something to the ash tree.

When is sacrifice a story of loss or initiation?

During the writing(with)Ash session, the circle was asked: “When is sacrifice a story of loss—and when is it a story of initiation?”

It’s a powerful question, especially in a culture that clings to the myth that we can have everything, all at once. But I don’t think that’s true. We live within constraints—of time, energy, body, and earth. Pushing past them, pretending they don’t exist, often leads us away from what truly matters.

Earlier this week, while walking along the Oslo coast with a friend, I shared my decision to take a sabbatical next year. A few years ago, my finances were in rough shape. I worked hard in a startup to stabilize things—but it came at a cost. My health suffered. Other parts of life were neglected. Now that I’m more stable, I want to reclaim my health, to re-center.

We often frame moments like burnout, breakups, or leaving a job as losses. And they are. But they can also mark the start of something else—an initiation into a new phase.

Nature shows us this again and again: loss is often followed by rebirth. Not a return to what was, but a transformation into something else. Something unknown.

Whether it’s better or worse—for me, for the land I’m part of—I can’t say. Only that it will be new. And sometimes, that’s enough.

‘Becoming the ash tree’

Every writing(with)plant session ends with a radical imagination exercise: participants are invited to shapeshift into our guest plant and write a short story from that new, rooted perspective. Some engage in dialogue with the plant, others become it entirely—but there is always a sense of exchange, of conversation. When I say “radical,” I don’t mean extremist. I mean it in the original sense of the word—from the Latin radix, meaning root. It’s about returning to the source, digging deep.

For 20 to 30 minutes, people write, draw, or scribble their way into becoming the ash tree. We often encourage them not to overlook the relationships their ash might have—with fungi, birds, soil, humans, ancestors. The ash does not stand alone. In becoming the tree, we are also invited to feel into its web of connections.

Becoming the emerald ash borer

In our writing(with)plants, we focus on one guest tree, but more as an easy entry point to dive into the complex web of life. We celebrate relational thinking. In the circles, different relations were mentioned, like the ash tree with the cherry tree in a Lithuanian story, but also the relation between the Emerald Ash Borer, the Ash and the purchase of machines in the USA to cut down the ash trees. Apparently, the Emerald Ash Borer came from Asia, but there he is not so harmful. However, for the Ash trees in especially North America this beetle seems to be deadly. We can see this beetle as the big enemy that needs to be destroyed with rockets, I mean cutting machines that kill the ash tree entangled with this beetle. But we can also make the exercise to shapeshift into the beetle and take distance from capitalocentric thinking.

‘being a stranger in a strange country’

By calling this beetle a pest and talking about an invasive species, and using war language, a whole network of banks and machine sellers found a new opportunity to create profit. Even when an ash tree might have one trace of the borer, the ash tree will die. I believe there is a danger to use labels like invasive species, strangers and others, to have an excuse to eliminate them, but I need a whole book to deconstruct the problem of fixation on static landscapes and not accepting change, loss and instead making space for grief and mourning. I know this deconstruction might bring me in analyses of human war and violence, and these conversations should take place in a dialogue.

‘Ambassadors’ feeling “out of time”

One of the participants shared that she’s part of an initiative where people act as ambassadors for other species, gathering in imaginative councils to speak on their behalf. She described the ash tree’s ambassador: wearing a hat adorned with leaves, changing with the seasons—an ever-shifting crown of color and decay, reminding us of time’s movement and nature’s cycles.

Another participant looked up the word ambassador. It comes from Middle English ambassadour, from Anglo-French ambassateur, and is related to the Old High German ambaht, meaning service.

That stayed with me. It made me begin to imagine Ash—son of Egle in our eco-myth—not as a politician in a grey suit, but as a different kind of ambassador. One who doesn’t represent power, but serves what needs to be served: the soil, the sky, the cycles of decay and renewal. An ambassador of interconnection, not transaction.

“The ash tree is blooming, to preserve his lineage”

Two participants joined our circle from a cemetery in Lithuania. One of them quietly observed: “The ash tree is blooming, to preserve his lineage.” He wondered aloud whether the ash somehow senses that hard times are coming—whether trees, like us, blossom most fiercely when something is at stake, perhaps even at their own expense.

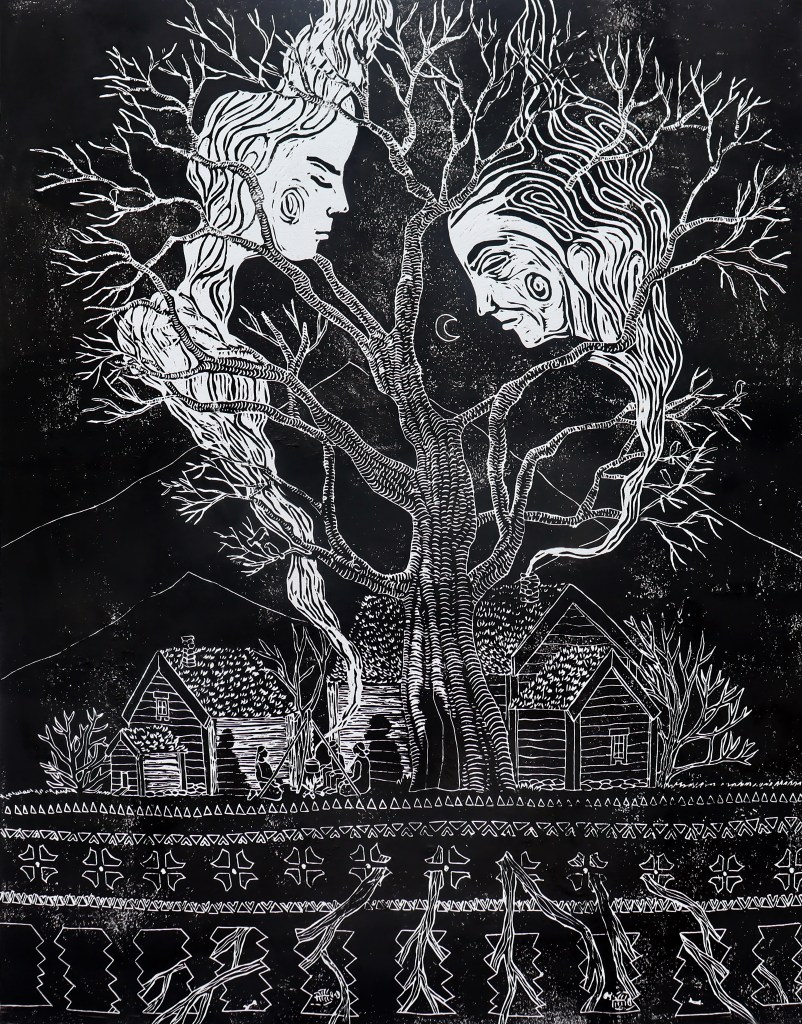

In this session, we found ourselves returning to the themes of lineage and heritage. I was reminded of an old drawing by Laura Brusselaers, made for one of my short stories, showing tree roots stretching deep beneath the soil—entwined with bones and skeletons. A sacred garden tree, echoing the Nordic tradition where trees serve as vessels of ancestral memory (see e.g. Sacred “Garden” trees of Norway and Sweden and Sacred garden trees, pt. 3: an ash tree in Gjøvik).

Joining the circle from a cemetery felt especially poignant given the timing—Easter, a season of remembrance and rebirth. Visiting graves, honoring the buried, connecting with the ancestors—it all becomes part of the story we’re telling with and through the ash.

We also spoke about belonging. One participant admitted she wasn’t sure if she belonged anywhere at all. Another shared how she preserves old traditions—not inherited directly, but passed down through her husband’s family to their children. Painting Easter eggs, for example, as a quiet act of continuity. Like writing runes, each stroke is a thread to something older, something still alive.

Painting the doors with blood

One of the participants in our circle comes from the Jewish tradition. In our gatherings, we are unafraid to be political—but we are careful not to confuse politics with religion. I grieve deeply for the innocent Palestinian lives lost today. And I also grieve for the horrors endured by Jewish people during the Holocaust.

For me, the common thread running through both is the damage caused by patriarchal systems—those ancient and ongoing hierarchies where some believe they are superior to others, entitled to domination. Where others must serve, obey, sacrifice everything to feed these modern gods of greed, control, and conquest. It is a system that demands loyalty without question, and in doing so, enslaves both the oppressed and, in more subtle ways, the oppressors.

If we re-root the old religious texts—strip away the dogma and power games—we may still find powerful metaphors that speak to liberation, resistance, and renewal.

This participant reminded us that Easter is tied to Pesach—Passover. A story of escape from oppression. I went to a Catholic school in Belgium, and spent time in a monastery—not for spiritual reasons at first, but because my mother worked there as a cleaning lady. The nuns, in their quiet way, taught me to type—like other women taught me to write, or to paint Easter eggs. I carry those teachings in my hands.

The story of Passover tells of Moses urging Pharaoh to free the enslaved Jewish people. Pharaoh, arrogant and unmoved, refuses. So God sends the angel of death to take the firstborn of every Egyptian household. But Moses is instructed to tell his people to mark their doors with the blood of a lamb—so the angel will pass over them. Protection through ritual. Freedom through sacrifice.

And here we are again, in spring, when the lamb reappears. When winter has ended, and the days stretch longer. A time to let go of what corrupts. To sacrifice what no longer serves. To free ourselves—again and again.

Ash tree as a hard and patient tree

In less than an hour and a half, all these themes and stories arrive—threaded together like roots seeking water. Another participant shared the observation that the ash is a patient and resilient tree. You receive all these threads, and then the creative part begins.

As someone dreaming up a hydrofeminist retelling of Eglė, alongside all the other artworks our collective is creating in Flowing with Eglė, these sessions have been invaluable. They help me shape my characters, clarify their wants and needs. And now, I feel I’ve come to understand Ash, the third child – shaped by grief, resistance, ancestry, and a slow-burning kind of devotion.

I suddenly saw him with the presence of Andrew Scott’s Priest from Fleabag—intense, tender, unpredictable. Let me share a first fragment of Ash in this new eco-myth.

RETELLING FRAGMENT #9: Why do we not have trees in the (baltic) sea?

The cemetery lay behind the dunes. As they walked, Ash remarked to his mother that the land felt empty and unprotected. “There’s so much more life in the sea,” he said, “in our palace, in the currents.”

His mother nodded. “Maybe we just need to slow down more,” she said. “Then you might see what’s really moving.” But she also agreed—life on land seemed to push them to move faster, to become blind to what surrounded them.

Still, they did not slow down. On land, the sun dictated the rhythm, and they had to follow it, so as not to upset her family—their hosts—any further.

Ash heard the ravens before he saw the linden and willow trees, and among them, the stones raised to honor the dead.

“What are those?” he asked.

“They are trees,” his mother replied.

“Why don’t we have them in the sea?”

His mother paused, surprised by the question. She realized they hadn’t seen any of these special trees in her uncle’s domain or along their path.

“There aren’t many left. They used to be women—the lovers of the men buried here. Long ago, women and men were more in touch with their origins. The men were buried and became ash and soil, and the women—who always outlived them—transformed back into trees.”

“Long ago? So that means…?”

“It means many people no longer remember where they come from,” she said. “We try to give our children tree-names, as a kind of spell. But they don’t transform anymore when the time is right.” She looked away toward the horizon. “Your father thinks it’s because, in our human lives, we’ve seen what happens to trees. How they’re cut down to build castles, wasted on things no one needs. So perhaps no one wants to become a tree in the next life—to become a slave form.” She gestured across the field. “But without the trees, the land grows more barren, and we are left unprotected. The invaders have found us, corrupting us with new ideas of what ‘progress’ means.”

She pointed to a nearby linden.

“That’s the youngest one. She’s probably a hundred years old. Since then, no one in this place has transformed into a tree.”

DIWO writing(with)ASH

Please download the slides here. Go through the questions and links. Let us know in the comments how this experience was.

Next session will be with little aspen

This session will be live, during the NSU summer symposium in Finland. Let us know if you would like to join us in Finland (Monday evening 21 July until Monday morning 28 July). Read more here: Join us in Finland (21-28 July) for learning with Trees, Rocks, Water, … perhaps Moomins.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.