Recently, I rediscovered a paper by Jaime Tatay, published in the journal Religion, while organizing my drive and considering the publication of a book about sacred trees based on a decade of research. The paper examines how local expressions of religion in Spain have creatively intertwined spiritual insights with popular devotions within ecologically significant settings, thereby contributing to the preservation of Spain’s rich biocultural heritage. It focuses on various Sacred Natural Sites (SNS), primarily Marian sanctuaries, and discusses how local “geopiety” and religious creativity have led to “devotional titles” linked to vegetation, geomorphological features, water, and celestial bodies.

“baptised paganism”: from Artemis, Diana, Isis, Cybel to MARIA

The connection between Maria and sacred wells doesn’t surprise me, as I’ve encountered similar stories in Belgium during my reflections on religious and spiritual traditions. See e.g. From Celtic source cult and tree devotion to worship of local female saints in Flanders. This is what I learned from Tatay:

The cult of Mary, described as “baptized paganism” (Benko 2004), was shaped by figures like Justin Martyr (100–165 CE) and became prominent from the 4th century, blending with ancient goddess cults like Artemis, Diana, Isis, and Cybele. Mary evolved into roles such as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven, incorporating elements like fertility and earth worship associated with the Magna Mater. This transformation led to the creation of sacred Marian topographies where natural sites such as water sources, mountains, and caves, previously dedicated to spirits or goddesses, turned into Marian sanctuaries.

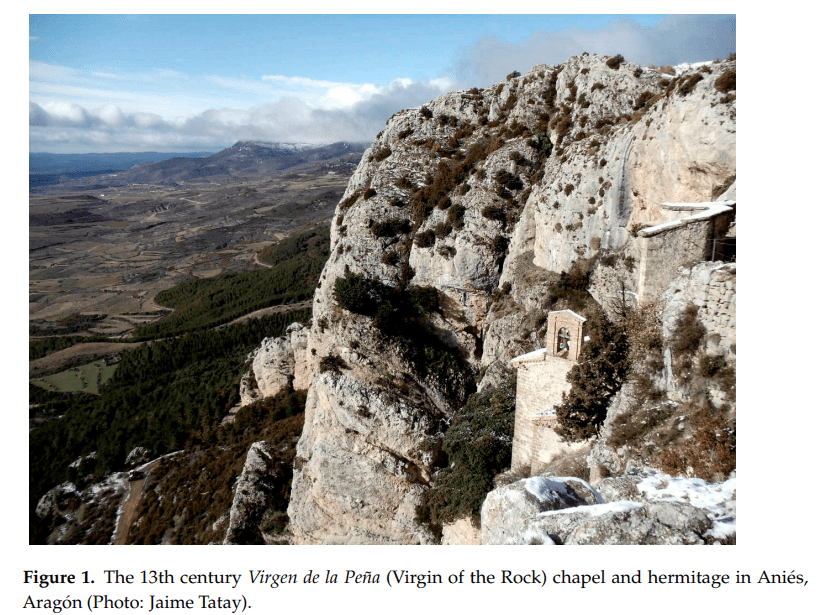

In Spain, the Visigothic kingdom preserved animistic and Celtic cults as folk practices, which were Marianized over time. The Roman Catholic Church repurposed Roman and pagan sacred sites into places of Christian worship, dedicating them to the Virgin Mary. By the 13th century, influenced by the Cistercian reform, Marian shrines proliferated across Spain, replacing older patron saints and incorporating hundreds of nature-related advocations like Rocío (Dew), Montserrat (Rugged Mountain), and Covadonga (Cave of the Lady). These sites, celebrated for miraculous discoveries and healings, helped universalize and then re-localize the Marian cult through distinctive titles and narratives of Marian apparitions.

Your to visit stops in your next spain trip?

- Montserrat Sanctuary: Nestled in the Parc Natural de la Muntanya de Montserrat, frequented by thousands of pilgrims, hikers, climbers, and tourists at the Benedictine Monastery. https://maps.app.goo.gl/7KCJbo4jMGbF7Eq8A

- Covadonga Sanctuary: Situated at the entrance of Picos de Europa National Park, near the popular grotto, draws numerous visitors weekly. https://maps.app.goo.gl/qmhDFMtqBshiU4QV6

- El Rocío Sanctuary: Located adjacent to Doñana National Park, attracts up to 1 million devotees during the main pilgrimage and thousands every weekend. https://maps.app.goo.gl/eHHbUPBENyKirNvT6

According to Tatay, All three are active Marian spiritual centers located within protected areas of significant ecological value.

Relationship between maria and trees (hint: ARTEMIS)

Artemis was revered as “the noumenal spirit of the forests which gives birth to a multiplicity of species (forms) that preserve their original kinship within the forest’s network of material interdependence” (Harrison 1992). However, the cult of Artemis declined in the 4th century during the reign of Theodosius, and her temple in Ephesus was closed in the early 5th century. This decline coincided with the rise of Mary’s veneration as Theotokos (Mother of God), which was officially recognized at the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE. Similar transitions from indigenous goddesses to the Virgin Mary, integrating elements like fertility and sacred trees, are also noted in Latin America. To read more about church forests, holy groves and sacred trees, I recommend to find one hour of time, brew some tea and read the paper: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/12/3/183

Deeply rooted

The paper also addresses the resilience of certain rituals and public expressions of faith in rural sanctuaries, despite mass urban migration, the questioning of “popular religion” post-Second Vatican Council, and rapid secularization over the past fifty years. Some of these traditions, dating back to the Middle Ages, have not only persisted but thrived, though they do not necessarily signify a move towards postsecularism.

Preservation of Biocultural Diversity and Strengthening Local Identities and Practice

Tatay suggests that Protected Area (PA) managers, regional governments, custodians, anthropologists, tourism scholars, and theologians should collaborate to address the management challenges faced by these popular SNS, ensuring their preservation for future generations. Biocultural heritage represents a fusion of biological and cultural diversity, encompassing knowledge systems, practices, and beliefs deeply rooted in the natural environment. Sacred trees and natural sites are quintessential examples of biocultural heritage, as they are often central to local customs, religious practices, and community identities. Recognizing and preserving these sites not only safeguards biodiversity but also maintains the cultural practices that have co-evolved with local ecosystems over centuries.

rEFERENCES

Tatay, J. (2021). Sacred trees, mystic caves, holy wells: devotional titles in Spanish rural sanctuaries. Religions, 12(3), 183. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/12/3/183

Do you want to learn more?

Sign up to a newsletter to receive blogposts and/or online workshops about Rewilding (female) saints. As you can see, a blogpost is written once a year, so this will be a very slow newsletter.

You can sign up via this link or by scanning this QR code:

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.