The eco+mythology winter symposium was dense with richness and layers. What I carried out of it will inevitably differ from what others took home. What follows is not a neutral report, but a situated retelling, one spoonful from a much larger soil soup.

The Cauldron: What Is Eco-Mythology?

We began with a question that stayed with us throughout the two days: what do we mean by eco-mythology?

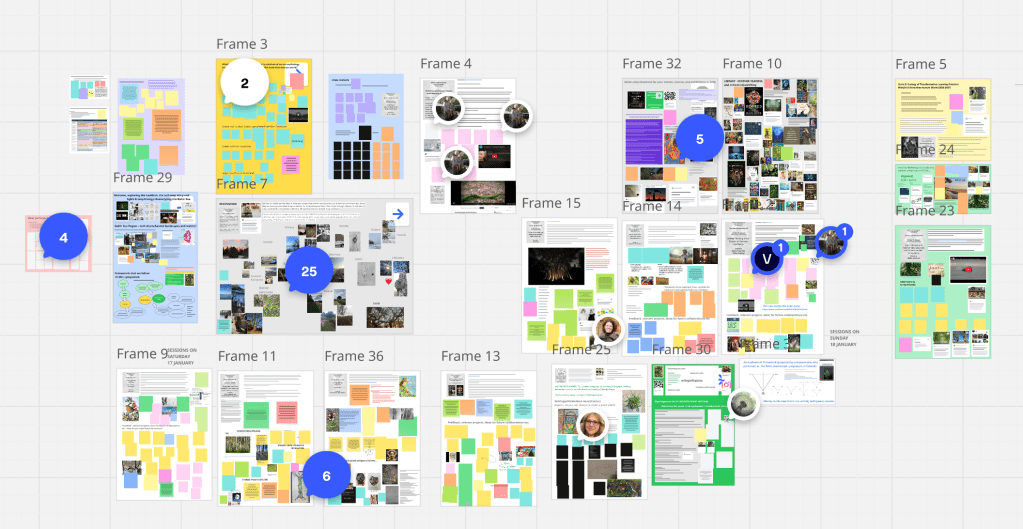

Before the symposium, presenters had shared their own definitions, which we collected on our MiroBoard, our shared digital cauldron. I exported this frame of definitions, because it already tells a story of plurality, friction, and shared curiosity.

To introduce the cauldron, I retold the folktale of stone soup, but transformed it into a soil story (read it here). In this version, everyone brings an ingredient, even those who feel they have “nothing to add.” The magic lies precisely there: through collective contribution, a nourishing soup emerges for the whole community. This metaphor framed our two days of co-creation.

I walked participants through several MiroBoard frames, including one on relationscapes, inviting everyone to introduce themselves through place and three relationships with the more-than-human world. On my own post-it, I wrote: Wendy, currently rooting in Norway, in relation with Lake Mjøsa, spruce trees, and mysterious huldra stones.

Thinking With Stories, Not About Them

Our first session was led by Alette Willis, who invited us into thinking with stories. She shared a British winter tale about a robin, explaining why some trees remain evergreen while others lose their leaves, a cautionary origin story.

Alette also grounded the storytelling in theory from her academic work (e.g. Willis et al 2022), presenting a triangle that connects story, dialogue, and experience. Psychological research shows that we connect to stories through lived experience; we project ourselves into them. Our reactions, she suggested, are not distractions. They are ingredients. They thicken the soil/stone soup.

This led to a rich discussion. Some participants read the story critically. Was there an element of punishment, when the trees that refused to help the robin suffered consequences? Are we projecting human moral concepts, like punishment, onto the more-than-human world? Or is a certain degree of anthropomorphising not only inevitable, but necessary to create connection and empathy?

If a story is too far from our “bed,” do we stop engaging with it? And yet… don’t we also love stories with consequences, stories that teach us something?

Photovoice: Stepping Outside the Cauldron

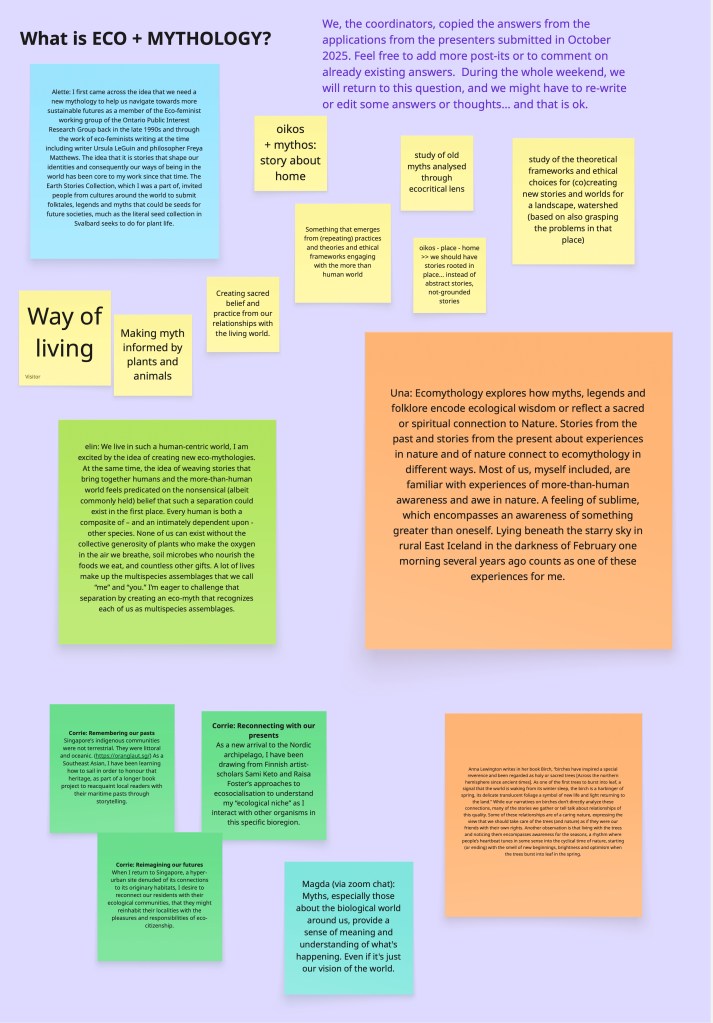

After this session, participants were invited outdoors for a photovoice exercise: take one or two photographs of your place, reflecting on what eco-mythology could mean there. We created a MiroBoard frame for uploading images and notes.

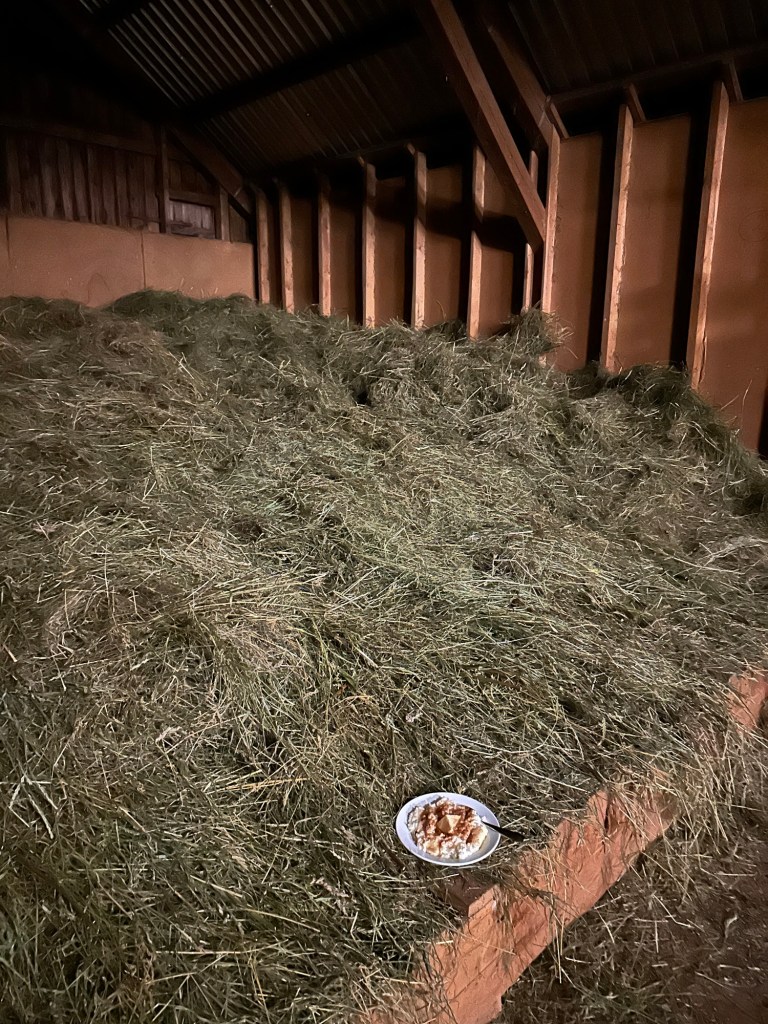

My photographs (used as illustration) came from my earlier blog post on Christmas rituals for farm gnomes in Norway, rituals of gratitude to land and invisible helpers.

Birch, Folk Songs, and Multispecies Selves

After lunch, Liene Jurgelane, Una Thorlaksdottir, and Yingying He foregrounded the birch tree, drawing on their work across Denmark, Finland, Iceland, China, and Latvia. One of them invited us to listen to a folk song. This mattered more than it might seem at first. Folk songs would return again and again throughout the symposium.

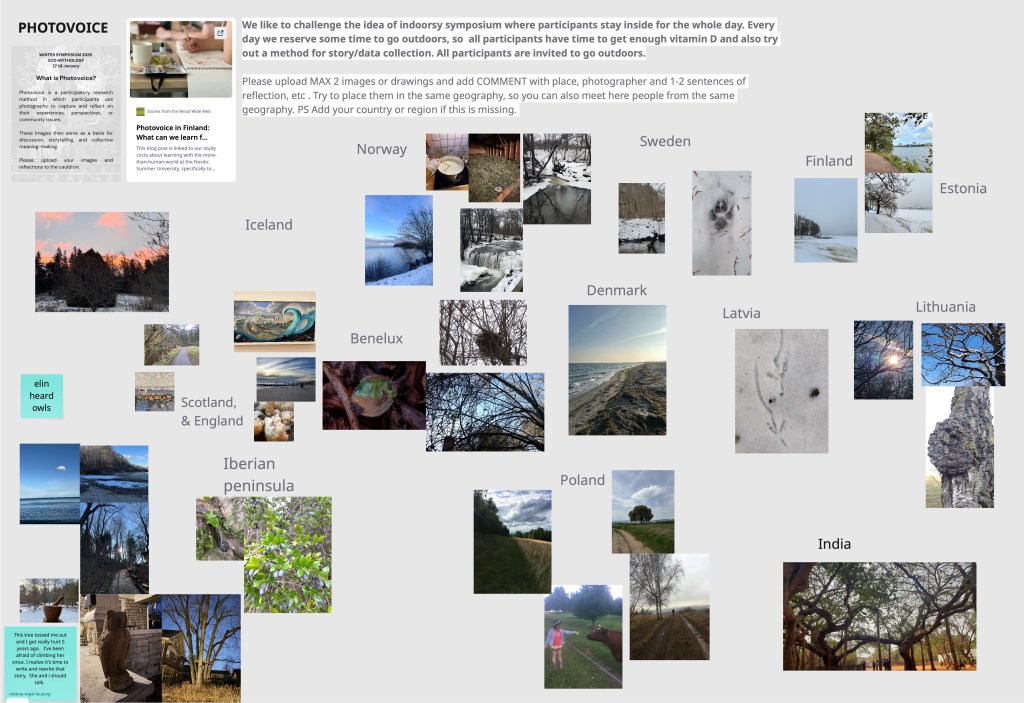

Later, elin kelsey and esmé johnson (mother and daughter) guided us through an artistic session on multispecies self-portraits, followed by Sage Borgmästers on ecofeminist myth-making. Sage explored mythopoetics through a comparative dialogue with the work of Clarissa Pinkola Estés and Sharon Blackie, guided by Donna Haraway’s reminder that “it matters which stories tell stories.”

We spoke about Blackie’s eco-heroine model... and yes, about AI.

I should note here: I am using ChatGPT to help improve the English of this blog post. As one participant put it, this is a grey zone. There is a difference between using AI as a tool and using AI to make meaning. As Vitalija reflected, AI used for practical purposes, like medical diagnosis, inevitably becomes part of our stories, and part of larger stories.

The soil soup kept thickening.

Writing (With) Plants and Toxic Binaries

We ended the first day with a writing(with)plants session facilitated by Lisa Sattell, once again inviting the Medusa Head plant into the cauldron. Some reflections will be shared in a later blogpost. I shared an early draft of a framework on the mythopoetic agency of plants as co-creators in design. If you are interested in the practice and want to join our free online Do-it-with-others writing(with)plant sessions, sign up here to our special newsletter.

At the end of the day, one discussion stayed with me deeply: the persistence of destructive, binary associations, like woman–nature–evil–dirty. This resonated with Patrycja Pichnicka-Trivedi’s book Countering Anthropocentrism: Vegetarian Vampires, Ecology, and Non-Human Subjects (2025), which I also reference in my upcoming care(work)book writing(with)plants. I will not dig further here. These thoughts deserve a whole book, perhaps a whole series.

Health, Poison, and Apothecary’s Questions

In my retelling of the soil soup at the beginning of the first day, my main female character (MFC) is a pharmacist. This might be a wink to one of my fellow coordinators.

On the second day, Vitalija Povilaitytė-Petri opened the cauldron. Drawing on her background as a pharmacist and expert in nature-based knowledge creation, she asked: What is health in a changing world? Where do our sources of health lie?

We spoke about microplastics, synthetic food ingredients, polluted water, air, soil, pesticides, radiation, stress. We spoke about living within capitalist (or perhaps techno-feudalist ?) systems, where we still need to pay rent, taxes, and food.

How do we care for ourselves and for life on Earth under these conditions? Which business models and ecosystems might sustain both humans and non-humans? How much poison is too much? How do we dose without becoming overwhelmed?

Vitalija and I will continue this work in a Master Design Studio (09-13 February) at Antwerp University and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, focusing on co-creating apothecaries.

Swamp-Thinking: Where Modern Narratives Sink

Our first keynote by Irena Chawrilska and Rick Dolphijn introduced swamp-thinking, from their upcoming book. Wandering the Baltic coasts of northern Poland, they became fascinated by brackish waters, wetlands, and swamps, spaces between life and death, fear and imagination. If there is one place where modern narratives fail – dualism, human exceptionalism, fascism – it is the swamp. They asked whether a transdisciplinary approach, combining literature, local storytelling, history, and biochemistry, could foster a less human-centred way of thinking.

We discussed the feminisation of swamps, which got later encountered by counter-examples of their masculinisation in Latvian folklore – in our second keynote (see later).

Swamps are full of queer fairy tales, so-called negative stories, weirdness, and excess. Why do right-wing politicians fear swamps so much? Why do they want to control them? In Shrek, Lord Farquaad dumps all fairy tales there. Perhaps the swamp is the perfect setting for an ecofeminist, hydrofeminist historical fantasy romance, following Sharon Blackie’s eco-heroine journey.

Mediators and parasites

Later sessions by Magdalena Tabernacka and Corrie Tan brought Polish imaginary creatures and banyan trees into the cauldron, raising questions about law, mediation, parasitism, and acknowledgement within artistic and knowledge-creation systems. Throughout the symposium, we encountered more-than-human mediators: birch, banyan, Medusa Head, imaginary beings, ticks, border guardians. What can we learn from them? How can they teach us to be better lawyers, architects, teachers, designers, planners, farmers, politicians, pharmacists, storytellers, academic researchers… ?

Who Gets Paid?

Magdalena Tabernacka’s session stayed with me in a very concrete way. It raised a question that often remains implicit in artistic, ecological, and mythopoetic work, yet shapes everything: how does one earn a living in relation with the more-than-human world?

What does income mean when imaginary beings, plants, landscapes, or spirits are involved in the work? Who is acknowledged, and who remains unpaid? Where do care, mediation, and (unintended) parasitic processes begin and end in artistic and knowledge-creation ecosystems?

As I was tasting the soil soup, I realised that this question deserves more space than I can give it here. I will therefore write a separate blog post in response to Magdalena’s session, provisionally titled: “How Can Imaginary and Other More-Than-Human Entities Earn Money?” I had already an exchange over e-mail with Magda. This blogpost is part of my own journey about co-creating frameworks for ecofeminist finances, which will also get introduced in the upcoming care(work)book.

The soup, once again, became thicker.

A Billion Folk Songs

Kārlis Lakševics, our second keynote speaker, reminded us that Latvia holds more than one million folk songs, many of them dialogues with the more-than-human world, or conflicts between water and stone.

When I look back at the cauldron, I do not only see, remember, or taste. I also hear. Cooking has a soundscape: sizzling mushrooms, boiling water, quiet simmering. Some things cannot be defined quickly. They need a thousand generations of grandmothers to articulate them.

Disenchanted Landscapes and Waste-Scapes: Where Does Eco-Mythology Begin?

During the final sessions, a recurring question surfaced: what about places that feel disenchanted?

Latvia is often described as one of the last Christianised countries in Europe, a place where enchantment still seems close to the surface, carried by folk songs, forests, and wetlands. As one participant reminded us, Sharon Blackie wrote her books and tools for privileged women who can afford to live in so-called enchanting wild places in Ireland and Scotland. Occasionally, our participants shared their experiences with the need for unraveling their privileges. Yes, this cauldron is still excluding some who also might want to drink the soil soup.

And what about highly cultivated landscapes like Denmark? Or Flanders, where I come from? What about industrial zones, logistics hubs, monoculture fields, highways, landfill sites, extraction zones, and polluted waters, waste-scapes rather than wild spaces?

Eco-mythology risks becoming exclusionary if it only speaks to forests that still feel sacred, or landscapes already coded as “magical.” One participant gently challenged this romantic tendency: if eco-mythology cannot speak to disenchanted places, then who is it really for?

This question also carries political weight. Narratives of enchantment can be appropriated by alt-right and nationalist movements (see an earlier exploration that I wrote some years ago: It’s VE day. Let’s talk about Nazis and the environment. When Elif wrote a blogpost about Trees in Tengrism and Turkish Mythology some years ago, she expressed in our preparation also – righteously- her concern that it might serve right-wing agendas), turning land into blood-and-soil mythology. Several participants expressed concern about how stories meant to resist fascism can be co-opted by it.

So how do we tell stories with damaged places…without purity politics? How do we attend to landscapes that are over-managed, polluted, or fragmented, yet still alive with more-than-human relations?

This question remains open…

What We Leave Behind: Palimpsests, Traces, and the Need for New Ceremonies

Toward the end of the symposium, my attention shifted from what we inherit to what we leave behind.

Several contributions evoked landscapes as palimpsests, places layered with traces of people, plants, animals, stories, and practices from different times. One of the participants, Ceallaigh S. MacCath-Moran, shared a journal entry about her visit to a sacred site in Scotland – with birch trees: a place where medieval graves sit alongside much older presences, where footsteps from many centuries overlap. Such places ask a quiet but persistent question: how do I show up here, now?

This question is not only about respect for the past, but about responsibility toward the present land. Many traditional ceremonies we refer to, solstice celebrations, seasonal rituals, emerged under very different ecological, social, and climatic conditions. Can we simply revive them unchanged?

I was reminded of a talk I attended during the autumn equinox in Lithuania, where a Lithuanian folklore professor argued that many ceremonies had indeed been interrupted, suppressed, or lost… and that reviving them is important. But he also emphasised something crucial: it is acceptable, even necessary, to reinvent songs, ceremonies, and rituals. Tradition, in this view, is not static preservation, but an ongoing, responsive practice.

This resonates with Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, a book I return to often, even as I hold its tensions. The novel was criticised within Silko’s own Indigenous community for revealing sacred knowledge. Yet one passage stayed with me: the medicine man (far from the stereotypical shaman figure) speaks about the need for ceremonies that do not yet exist. The world changes, he suggests, and ceremonies must sometimes be invented because old ones no longer meet the conditions of the present.

This raises difficult but necessary questions. Who invents ceremonies, and for whom? How do we avoid extraction, appropriation, or spiritual tourism? How do we calibrate rituals not to our own longing for meaning, but to the actual needs of the land, especially land that is damaged, polluted, or overworked?

Rooted Hospitality: What Comes Next

This is not the end.

We will gather again for a week-long symposium in Latvia. You can join our circle 5, which will focus on eco+tones.

However, I also want to draw attention to another circle, with whom we collaborated in the summer symposium 10, in Finland, exactly, as our goals and interests are so close. Our sister circle 10, Decolonising the Anthropocene through Artistic Research has a call for The Power of Ritual: Artistic Practises and Spiritual Knowledge in the Anthropocene.

Deadlines for applications of both circles are April 1st.

In circle 5, we are already dreaming of an online eco+mythology 2.0 in autumn, with a focus on Lithuania.

At some point, elin introduced the idea of radical hospitality. If “radical” is often misunderstood as extreme, let us return to its root: rooted hospitality. Temporary sanctuaries, because everything is temporary, grounded in care, relation, and the wood wide web.

If you feel called to co-create such sanctuaries, in whatever form and place, let us know. The cauldron is still warm.

Sign up here to our CIRCLE 5 newsletter to receive the announcements of the next symposia and relevant blogposts.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.