The Baltic Sea is full of ironies. The more I engage with it, through practice, theory, and fiction, the more I realize how little I truly know, and how much there is still to learn from its contradictions. This blog post reflects on an experimental Fishbowl session held during a Baltic Sea symposium in Poland, explored through the lenses of Donna Haraway and Félix Guattari.

Baltic Waterscapes

On Monday 13 and Tuesday 14 October 2025, the Academic Centre of Polish Language and Culture for Foreigners of the University of Gdańsk and the Centre for Sustainable Development of the University of Gdańsk in cooperation with the University of Utrecht organised Interdisciplinary Symposium “Baltic Waterscapes: Entanglements in Natureculture” at the University of Gdańsk.

Situating ourselves at the Baltic coast, we aimed to reflect on the entanglements of nature and culture at large — what Donna Haraway calls natureculture — with a particular emphasis on the symbolic, material, and political significance of water today. This symposium offered a space for interdisciplinary dialogue, bringing together philosophers, sociologists, geologists, scholars of literature and culture, philologists, curators, artists, and representatives from cultural institutions and NGOs.

A fish bowl

Vitalija and I decided to do a fishbowl, like we did in the NSU summer symposium in Finland, but this time with the novelty of a role play >>

It is an experiment in performative arts and democracy. Haraway’s natureculture refuses the split between nature and culture, insisting that beings (including humans, critters, forces, technologies, myths) are always co-constituted. This exercise is, in many ways, a living enactment of this concept, a a collective becoming-with.

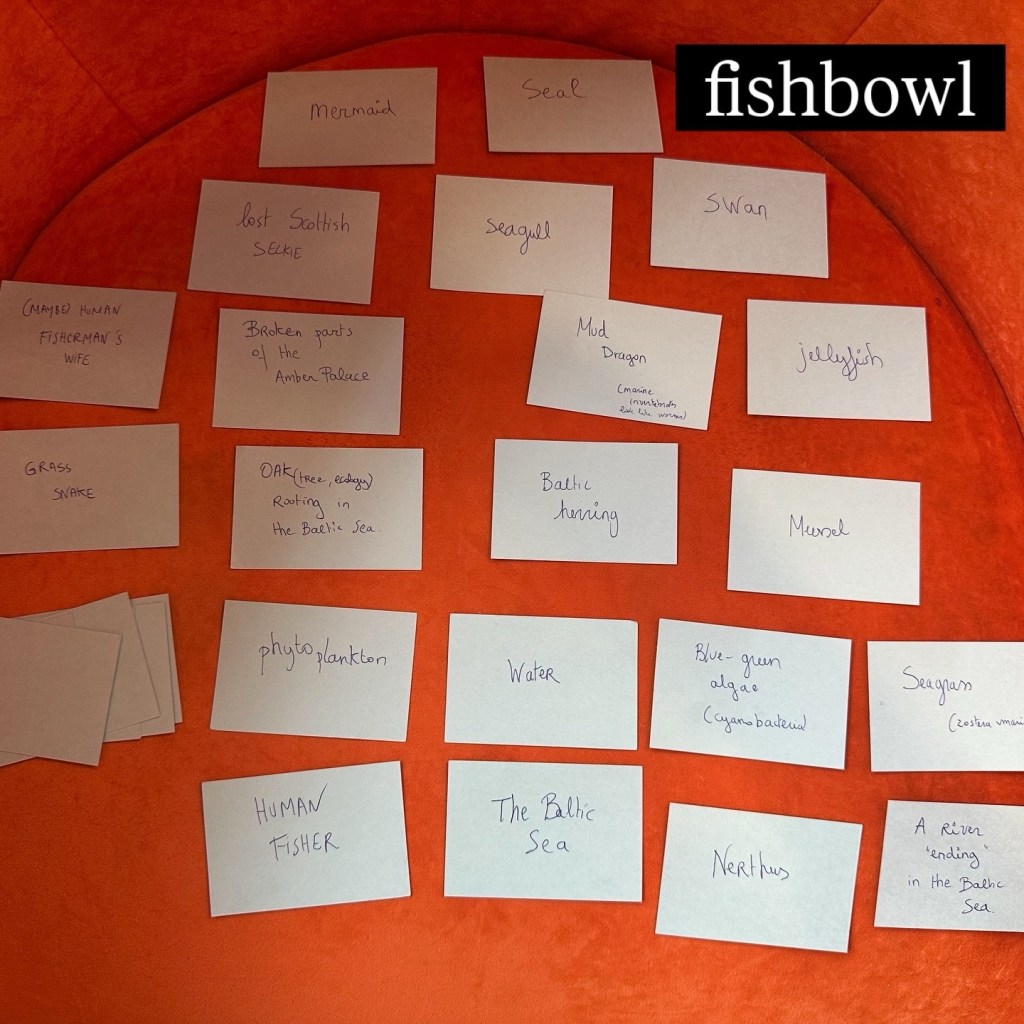

What did I put in the fish bowl?

During the first hours of the symposium, often inspired by the critters and forces mentioned by previous presenters, I wrote names on cards. I also left some cards empty … for if people wanted to chose their own critter.

Nobody created their own character. These characters talked in this 35 minute long experiment:

- Mud dragon

- Baltic Herring

- The Baltic Sea

- Human fisher

- A river ending in the Baltic Sea

- Jellyfish

- Lost Scottish Selkie

- (Maybe) human fisherman’s wife

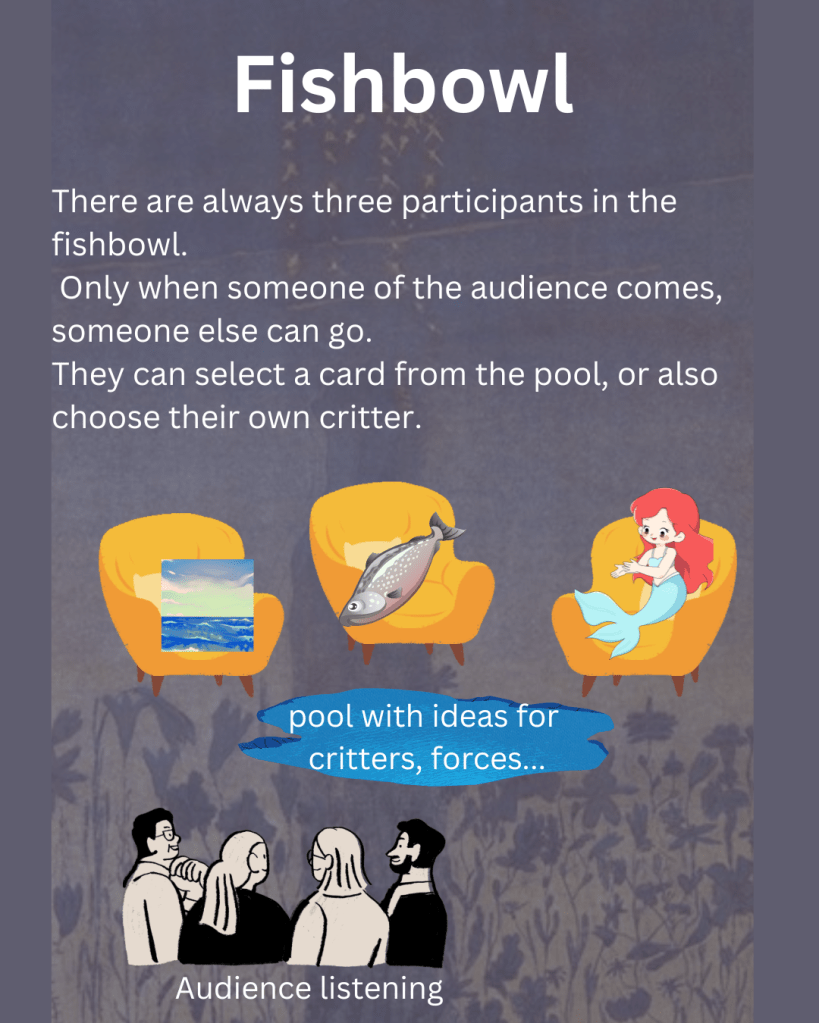

tHE BOUNDARIES – SOME RULE SETTING

My role was to establish the initial rules of the Fishbowl and to take notes for later reflection. Throughout the session, I also acted as a kind of facilitator, “stirring” the Fishbowl by inviting listeners to step in and replace one of the critters. Toward the end, however, I found myself tempted to join the circle as well … drawn in by the performative energy of the moment. I admit, I enjoy playing a bit of theatre.

The Fishbowl method has clear advantages, but also certain limitations. Participation depends greatly on the willingness of individuals to step into the circle; if people are shy, they may hesitate to join. It remains uncertain whether the use of masks or role-play dynamics might encourage more introverted participants to engage more freely. I did not, however, conduct any form of personality assessment to explore this further.

What was ‘said’ in the fishbowl? Reading it through Haraway’s lens

Entanglement of Species and Stories: The characters, the Baltic Sea, Mud Dragon, Baltic Herring, Human Fisher, Selkie, River, Jellyfish, all blur the line between human, mythic, and ecological.

- When the Baltic Sea “files for divorce” and resists feminization, the sea is not a passive environment but a subject with agency, trauma, and a voice.

- This “marriage” to Poland and the gendered language critique directly recalls Haraway’s argument that naming and metaphors are acts of power: to call the sea “she” or “mother” is not innocent. It domesticates and humanizes a force that resists domestication.

Critters and Companion Species: The Mud Dragon and Baltic Herring negotiated cohabitation; “helping each other to get rid of the noise of boats.” This is a multispecies alliance, an example of what Haraway calls companion species: co-existences that require ongoing negotiation, not harmony.

Their conversation exposes the friction between human infrastructures (boats, radiation, fishing) and nonhuman life, revealing that collaboration across species must also reckon with histories of harm.

Language and Translation: The interruption about “which language we should speak: English, one of the other human languages or nonhuman” highlights Haraway’s concern with translation and response-ability: the ethical and linguistic challenge of learning to speak-with rather than about.

Against Anthropomorphism, toward Relational Imagination: I noted something about “falling into stereotypes” and “anthropomorphism” which aligns with Haraway’s caution: representation of nonhumans often reproduces human hierarchies. Yet, Haraway might argue that total avoidance of anthropomorphism is impossible; the task is to do it critically … to make space for partial connections, to know that the “Mud Dragon” is both human-imagined and materially entangled.

Reading through Haraway’s Natureculture Lens: This fishbowl was a naturecultural laboratory … a rehearsal of what it means to think and feel with the Baltic Sea’s more-than-human collectivity. It dramatizes becoming-with rather than speaking for; it reveals language, gender, and myth as ecological forces themselves.

Reading through Guattari’s Three Ecologies Lens

As this symposium also celebrated the Polish translation of Guattari’s Three Ecologies, let’s also engage with this lens.

Guattari identified three interlinked ecologies:

- Environmental ecology (the planet, ecosystems), which I often link with the academic field of industrial ecology

- Social ecology (institutions, community relations), which I often link with the academic field of political ecology

- Mental ecology (subjectivity, affects, imagination)

Environmental Ecology: The Baltic Sea’s voice brings environmental degradation to the surface: ship noise, radiation, pollution. The “mud,” “flow,” and “streams” invoked by the Mud Dragon contrast industrial extractivism with organic movement. These exchanges make ecosystemic suffering speakable, but through affect and narrative rather than scientific discourse.

Social Ecology: The presence of the Human Fisher, Selkie, and River introduces relational politics. I noted words like marriage, seduction, national borders, foreignness. These are not just character dramas but metaphors for geopolitical and colonial entanglements around the Baltic: fishing economies, national claims (“married to Poland”), and the unequal distribution of environmental harm. The social layer exposes the anthropocentric logic of ownership and consumption (especially the human fisher using words like “new cuisine,” “dining culture”) and how it intersects with nonhuman exploitation.

Mental Ecology: This is perhaps where the experiment shines: by staging these encounters, I invited participants to recalibrate their subjectivities.

- When humans play critters, they momentarily reconfigure their sense of self: it might be seen as a Guattarian “molecular” shift in perception.

- The awkwardness, humor, and discomfort (“I got lost,” “I don’t feel comfortable here”) are symptoms of this reterritorialization. It might be part of the character’s story, but might also express their own feelings in the experiment. The play generates new affective ecologies, spaces for empathy and imagination that can contest capitalist and anthropocentric mentalities.

Ecosophic Assemblage

Guattari’s goal is an ecosophy, a practice that connects these three ecologies in a process of heterogenesis (becoming-other).

The fishbowl does precisely that: it creates a temporary micro-ecology where participants’ subjectivities, social imaginaries, and environmental awareness are entangled and renegotiated.

The interruptions, language confusion, and anthropomorphic slips are not failures but ecological signals … evidence of boundaries being tested.

Of course, all the participants who joined the Fishbowl are well-versed in Haraway and Guattari, so it is perhaps unsurprising that there might be layers of theoretical self-awareness shaping their performances.

A performative ecosophic ritual

- It composts human subjectivity into multispecies relationality.

- It decenters the human voice while acknowledging the impossibility of total escape from human mediation.

- It embodies the very task Haraway and Guattari propose: to learn to live and think otherwise, through art, story, and embodied practice.

| Theme | Haraway (Natureculture) | Guattari (Three Ecologies) |

|---|---|---|

| Gendering of the Sea | Critique of gendered metaphors that naturalize domination | A sign of mental ecology shaped by patriarchal capitalism |

| Nonhuman speech | Experiment in response-ability and multispecies communication | Re-patterning mental ecology, opening new semiotic flows |

| Pollution / Noise / Radiation | Material-discursive entanglement of human and nonhuman histories | Environmental ecology destabilized by technocapitalism |

| Performance setting | A practice of “worlding” and “staying with the trouble” | An ecosophic workshop aligning mind, society, and environment |

| Awkwardness / discomfort | Productive tension in becoming-with | Mental deterritorialization necessary for transformation |

This experiment can be seen as part of our Flowing with Eglė – Project and our NSU study circle: Learning with the More-than-human.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.