In August 2025, I attended the International Ecoliteracy Research Festival, held at the enchanting Himmelberggaarden in Ry, Denmark. A few days beforehand, I learned from Anika, a wandering “serial rooter” currently based in Aarhus (just a 30-minute train ride from Ry), that this Nordic center of inspiration is connected to a mythological place. Himmelbjerget (literally “Sky Mountain”) is said to be the home of Heimdall, a god from Old Norse mythology. And yes, this mythical place exists … right here in Denmark. I love it when geography and mythology meet.

About the festival location: eco-mythology in practice

On their website, Himmelberggaarden describes their vision:

“Our intention is to lead by example. We are transitioning our operations to renewable energy, growing our own vegetables and eggs, fostering biodiversity and insect life in the area, and hosting bee colonies. We minimize waste wherever possible and recycle or circulate resources further in order to reduce our everyday CO₂ footprint.

We don’t claim to have the final recipe. We are an experimentarium—a living experiment—aiming to inspire long-term holistic thinking and positive development in areas such as resilient communities, innovative leadership, social innovation, well-being, and cross-sector collaboration that transcends both public and private boundaries as well as national borders.”

About the place: Heimdall’s home

Just 15 minutes on foot from the venue of the Festival lay this mythological site. Naturally, I set aside some time to visit it 🤓.

🥾 A well-marked hiking trail led me back toward Ry station, where I caught the train to Aarhus. The walk was easy and took me less than two hours.

And yes, Heimdall found his way into my writing during the festival’s place-based workshop (see later). I experimented with weaving in “early warning signal” thinking, drawing connections to environmental studies and disaster management.

About the International Ecoliteracy Research Festival 2025

From the website of the organizers (SDU- CUHRE research group), the festival was described as follows:

“The festival celebrated the meeting of people, nature, and life-friendly visions for the future.

Through presentations, workshops, play, and communal activities, we aimed to create a space for dialogue, learning, and action.

It was an outdoor festival, centering the more-than-human world without extensive use of electronic devices.”

And of course, there was vegan food.

I enjoyed it deeply—

food for the body,

and food for the soul.

I organized a writing(with)plants workshop with the blackberry as our guest plant, and in the process I connected with remarkable humans and nonhumans alike.

One of the participants was a Danish professor emeritus who also joined the workshop. Later, over dinner, we had a long and inspiring conversation about working with non-human characters in fiction—such as in Tussenland, my latest book (only in Dutch). We discussed how writing choices can be informed by ethics and pedagogy.

She shared that she was writing her own work of fiction, grappling with the theme of ecocide in Denmark and foregrounding plants like eelgrass. I am very curious to read it (I can manage Danish or Norwegian after drinking the right plants—like green tea).

From her I also learned that Denmark—together with Bangladesh—is considered the most “cultivated country” in the world. More than the Netherlands or Belgium? I asked, surprised. I knew Denmark was often criticized by environmental scientists and humanists (for example, regarding industrial pig farming), but I hadn’t realized the country had less “wild” land than the Low Countries.

At the same festival, an IPCC author also reminded us of the rising sea levels and the growing frequency of environmental disasters 🌊…

The festival was, in many ways, about both pleasure and pain.

What is Ecoliteracy?

“Being fluent in a language means being able to speak with others about the land in that language,” a participant remarked. If fluency in a language means being able to speak with others about the land, then ecoliteracy could be understood as learning to read, interpret, and converse with the living systems around us. It is not only knowing the names of plants, animals, and landscapes, but also recognizing the relationships that sustain them—and us. Ecoliteracy invites us to listen to the stories of rivers, soils, and seasons, and to carry these stories into dialogue with human communities, weaving ecological awareness into culture, ethics, and everyday life.

From Ecoliteracy to Ecomythology

Going from ecoliteracy to ecomythology means moving beyond understanding ecological systems in a scientific or practical sense, toward weaving them into the stories, symbols, and myths that guide how we live. Ecoliteracy equips us with the ability to recognize patterns in the land, the seasons, and the interdependence of life. Ecomythology takes this further by giving those patterns narrative and cultural meaning, so they become part of how communities imagine themselves and their place in the world. Where ecoliteracy teaches us to “read the land,” ecomythology invites us to “story the land,” integrating ecological knowledge with imagination, ethics, and belonging.

place-based writing for eco-imagination

Tommaso Reato, a professor specializing in creative writing, joined my Writing with Plants session, and afterwards we had a brief conversation about the methodology. He remarked on how unique it was to share writing circles with plants—always with the thread of a specific plant to focus on—and how fascinating it was to see this practice nourish creative writing. In his own research and practice, he has facilitated similar workshops, but usually lets participants begin writing directly, without first drawing on the collective wisdom of the group.

On the final day of the Ecoliteracy Festival, I had the chance to join his workshop, “Place-Based Writing: Twisting Writing Toward Eco-Imaginative Practice.” (Source: abstract and bio, click here)

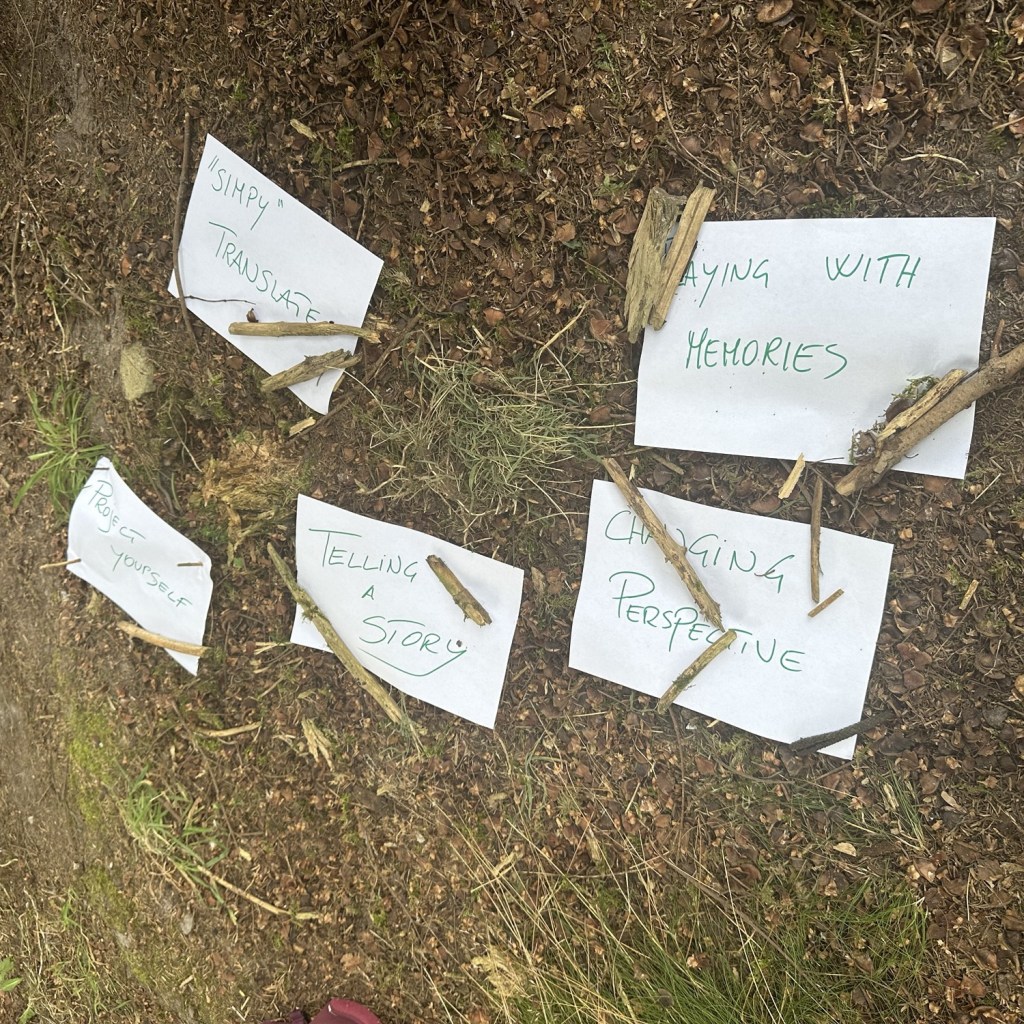

During this session, he shared some insights into the methodology behind his environmental education research with children. After the workshop, he collected both drafts and finished stories, and also conducted interviews to uncover what remained outside the written texts. We do not follow this approach in the Writing (with) Plants sessions, but I am currently gathering science fiction stories for a European workshop on bio-based circular architecture. It was encouraging to hear that my own ideas for evaluating the educational and ecoliteracy impact of such storytelling practices are also being explored by other researchers. He told us that he recognised five patterns in all the creative work:

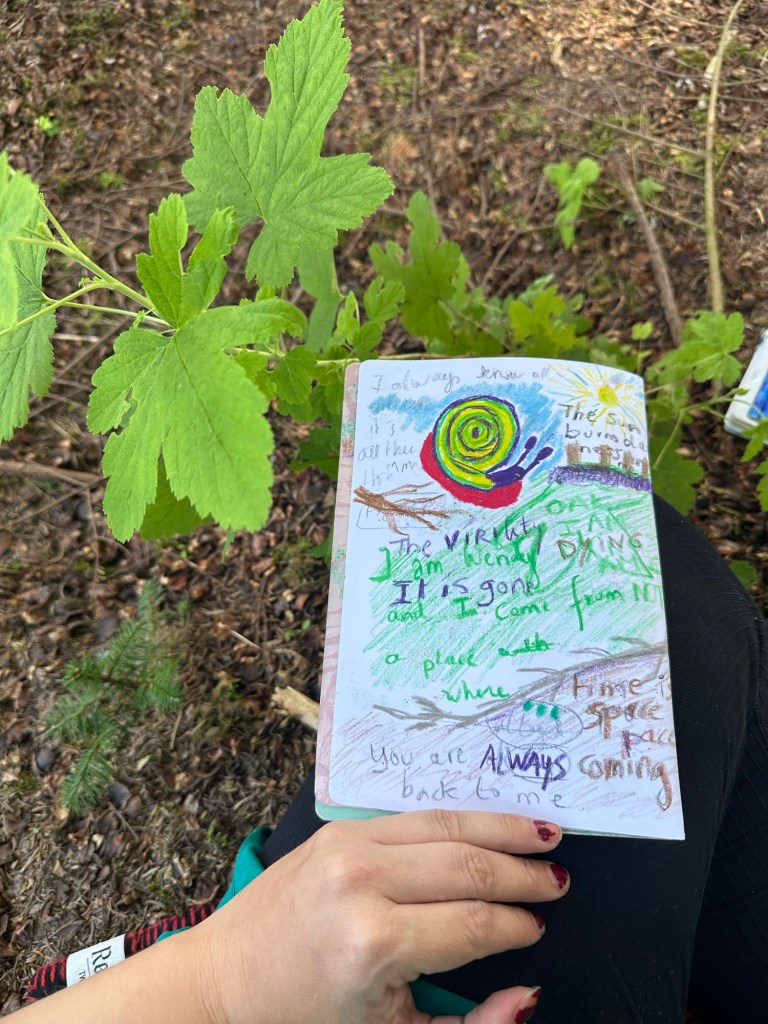

From Tommaso’s invitation ‘Inventing a new plant’ to an entry into a new eco-mythology for sky mountain

What I enjoyed most was simply letting myself imagine. Tommaso invited us to connect with a plant at the outdoor site in Himmelbjerget, where our workshop took place, and to invent a new name for it. In an earlier writing workshop I had already connected with a small plant, and I returned to it this time. I don’t know exactly why or how (or perhaps I do—after all, I was sitting in a place full of stories and legends), but I suddenly received a whole story and a name for this being: Heimdall’s Eyes.

In Old Norse mythology, Heimdall was known for his extraordinary sight, which made him the guardian of Bifröst—the rainbow bridge connecting Asgard, the realm of the gods, with Midtgård, the world of humans. Himmelbjerget, “Sky Mountain,” is itself tied to myth as the mountain of the gods, said to lie just beyond the rainbow bridge.

I wasn’t taking many notes those summer days; instead, I was mostly drawing. And in my imagination, Heimdall appeared not as a stern watchman but as a highly sensitive, neurodivergent fairy, living in a rainbow-gated community. Just as Odin had the help of his ravens, Heimdall was aided by these plants I named Heimdall’s Eyes. They acted like early warning signals, bio-indicators of environmental change. If their color turned red, it meant that Ragnarök was near.

In my carrier bag

In the end, what I carried home from these workshops was more than drafts or stories. It was a renewed sense of what eco-imagination can do. Through practices like place-based writing and writing (with) plants, we learn to notice differently, to listen with patience, and to let new voices (human and more-than-human) enter our stories.

This is where ecoliteracy grows roots: in learning not only to read the land but also to speak with it. And when these practices stretch further into the realm of ecomythology, they remind us that myths are not just relics of the past; they are living frameworks for how we might imagine and inhabit the future.

Writing circles become seedbeds where ecological knowledge and cultural imagination meet, spaces where stories can guide us toward more attentive, more resilient, and more enchanted ways of being in the world.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.