In this blog post (20 minutes reading time, please brew some tea and enjoy), I share reflections on my short holiday visit to Skagen in Denmark, the place where the Baltic Sea meets the North Sea.

Here, amidst the stark beauty of this landscape (where I experienced a personal-mystical travelogue), I contemplate desexualized lives that persist in such a wasteland and search for hydrosexual instructions to re-enchant both life and the world. Along the way, I engage with the theories of Silvia Federici, Ewelina Jarosz, Astrida Neimanis, and Cecilia Åsberg, drawing inspiration for my ongoing project: the hydrofeminist ecomythology of Eglė.

wHERE IS SKAGEN?

Skagen is the northernmost town in Denmark. The name was applied originally to the peninsula but it now also refers to the town. The settlement began during the Middle Ages as a fishing village, renowned for its herring industry. Thanks to its seascapes, fishermen and evening light, towards the end of the 19th century it became popular with a group of impressionist artists now known as the Skagen Painters. I arrived there by train (via Aalborg).

At the headland at Grenen, commonly but erroneously believed to be the northernmost point of Denmark, the North Sea and the Baltic Sea meet. Because of their different densities, a clear dividing line can be seen. As a result of turbulent seas, beachings and shipwrecks were common.

Skagen feels like the perfect, magical edge where one can engage with water, optics, summer light—and the intertwined themes of life, death, and marriage. I stayed there for three days to work on my Eglė and Tussenzee books, focusing especially on envisioning the less-detailed parts of Eglė‘s story: her marriage and the birth of her four children. Perhaps this part of the myth was glossed over because it was filled with love and ecosexuality, lacking the tension and drama that make stories marketable. Or perhaps it was so intimate that it had to be censored.

For me, the meeting point of the two seas carries a sexual charge of its own. During those days, I wandered and mused, explored the town, learned more about the Skagen Painters, what lured them to this place, and I felt the beach and the water, and wrote—immersed in the sensuality and mystery of the place… and magical things happened to me.

dESexUALIZED LIFES IN dISENCHANTED LANDSCAPES

At the moment, there is no human lover in my life, but that does not mean I am without a sexual life. The more I reflect on it, the more I realize that making time for sexual experiences is, in itself, an act of resistance. In the following sections, I will delve into the concept of eco/hydrosexuality, but first, I need to address why a desexualized life might be a symptom of a broader toxic system.

In recent months, I have been engaging deeply with the work of Silvia Federici, a scholar renowned for her research on the history of the commons and feminist movements. In her book Re-enchanting the World, I came across a passage that encapsulates the very problem at the heart of this blog post:

“Capital has long dreamed of sending us to work in space, where nothing would be left to us except our work machines and rarified and repressive work relations. But the fact is that the earth is becoming a space station where millions are already living in space colony conditions: no oxygen to breathe, limited social and physical contact, a desexualized life, difficulty of communication, lack of sun and green … even the voices of migrating birds are missing. Our own bodies are being enclosed. Appearance and attitude are now closely monitored in jobs in the ‘service industries,’ from restaurants to hospitals. Those who ‘work with the public’ have their bodies—from their urine to their sweat glands to their brains—constantly checked. Capital treats us today as did the inquisitors of old, looking for the devil’s marks of the class struggle on our bodies and demanding that we open them up for inspection. The duty to look pleasant and acceptable explains workers’ increasing recourse to reconstructive surgery.” (Federici, 2018)

This passage resonates deeply with the ways our bodies and desires are disciplined under capitalism. The erosion of sensuality and the constant surveillance of our physical selves are not incidental—they are mechanisms of control that strip us of autonomy, joy, and connection. Reclaiming our bodies, our pleasures, and our relationships with the more-than-human world becomes not only an act of self-care, but also a radical form of resistance against this systemic enclosure.

Marriage and The erotic experience of pain – horse flies, mosquities, DUNE GRASS and other vampires

In the weeks leading up to my visit to Skagen, I found myself thinking about love, erotic experiences, pleasures, and the pain bodies we carry in this disenchanted world.

I had written a piece on transferring pain to nail and fever trees—Summer (Fever) Tree. Involving trees in the experience of pain makes sense within a relational worldview: we are the trees, and the trees are us. Together, we carry pain, suffering, death, and love. This made me wonder about the marriage between Eglė and the snake (the Baltic Sea). Did this union mean she began to feel the snake’s pain as her own, and the snake—he, she, or perhaps beyond binary terms—began to carry hers? Or was the marriage less an exchange and more a remembering of relationships that had always existed, invisible until the snake tricked her under the water?

In Finland, some weeks earlier, I let a horsefly pierce my skin. I felt the sharp pain, knowing it would not itch like a mosquito bite. Mosquitoes, ticks, vaccinations—all forms of penetration that leave traces on the body. Last year, I also shared reflections with Heide and Vitalija, the co-midwives of the Eglė project, about the experience of being bitten by mosquitoes—about letting them bite you while remaining aware of the risks, such as contracting a dangerous disease like malaria. Perhaps the risk is lower in Denmark, where Heide was bitten, yet it is steadily increasing due to climate change and the spread of hitchhiking mosquitoes traveling on airplanes. News from Belgium in 2020 (yes, I still remember) about a couple who died from malaria, likely contracted near an airport, is a stark reminder of how these risks are shifting and becoming part of our immediate environments.

At the same symposium, I was confronted with the statistic that every month we absorb as much plastic as the weight of a credit card into our bodies, and around 20 grams of microplastics settle into our brains. I don’t even want to imagine how many grams of plastic have accumulated in the Baltic Sea. It seems that penetration and sex are always shadowed by the risk of death—a thin line between Eros and Thanatos. In Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory (and yes, it seems impossible to write a blog post on this topic without mentioning Freud), Eros and Thanatos represent two opposing fundamental drives within human beings. Eros, the life instinct, fuels love, creation, and the urge to preserve life, while Thanatos, the death drive, pulls toward aggression, destruction, and ultimately, the desire to return to an inanimate state.

In Skagen, I got pricked by dune grass. The wind was moving it in a way that it pierced me. In addition, I encountered a baby viper, and had not stepped on this, because earlier dried toilet paper had drawn my eyes to the ground.

This summer, while reflecting on these themes, I also returned to my old notes on love, pain, annihilation, and penetration—some of which I had explored in my academic article on Finding Satoyama. Watching The Apothecary Diaries, I was struck by the final scene of the second season, where the main male character bites the female character. Both carried their own traumas, both struggled with their emotions. Some might see the bite as troubling, but I found it erotic. It recalled the ambiguous allure of vampires, the unsettling dynamic of S/M in for example series as True Blood (that I watched secretly, because there was this shy Catholic good girl that not wanted that others knew I watched such erotic shows) that had once troubled me but now invites me to think differently.

Does marriage mean sharing pain? Does it mean dying—a process of annihilation? Perhaps both. During this short holiday, I decided to read more about the older terms surrounding exosexuality and hydrosexuality, seeking instructions for re-enchantment.

Being an ecosexual, Being a hydrosexual

In one of the most recent publications by Ewelina Jarosz, editor of the book where I contributed a chapter on Eglė’s ecomythology, she engages with Stephens and Sprinkle, authors of Assuming the Ecosexual Position: The Earth as Lover (2021). They describe “ecosexual” as a self-defined identity that views nature as romantic, sensual, erotic, or sexy, and sex as an ecology beyond the physical body. Expanding on this, Ewelina introduced “hydrosexual,” a term emphasizing more-than-human sensuality through fluidity and relationality. Grounded in hydrofeminism (Neimanis, 2017) and queer ecologies, it uses watery thinking to disrupt what Åsberg (2021) calls the “hegemonic notion of the autonomous and bounded human subject,” amplifying hydrophilic logic (Jarosz, 2015).

In the myth, Eglė becames a hydrosexual. If I want to retell her story, I need to also explore the hydrosexual with/in me. While I greeted the Baltic and the North Sea, or both (are they really separated entities?), I knew I had to spend more time watching the water, trying (but probably never succeeding) in understanding the hydrophilic logic.

Summer light

According to wikipedia, Skagen’s long beaches were exploited in the landscapes by the so-called Skagen Painters.

P.S. Krøyer, one of the best known of the Skagen painters, was inspired by the light of the evening “blue hour”, which made the water and sky seem to optically merge. Everything becomes a mirror. Oh, mirrors, they are powerful tools for self-sabotage, but also deep reflection.

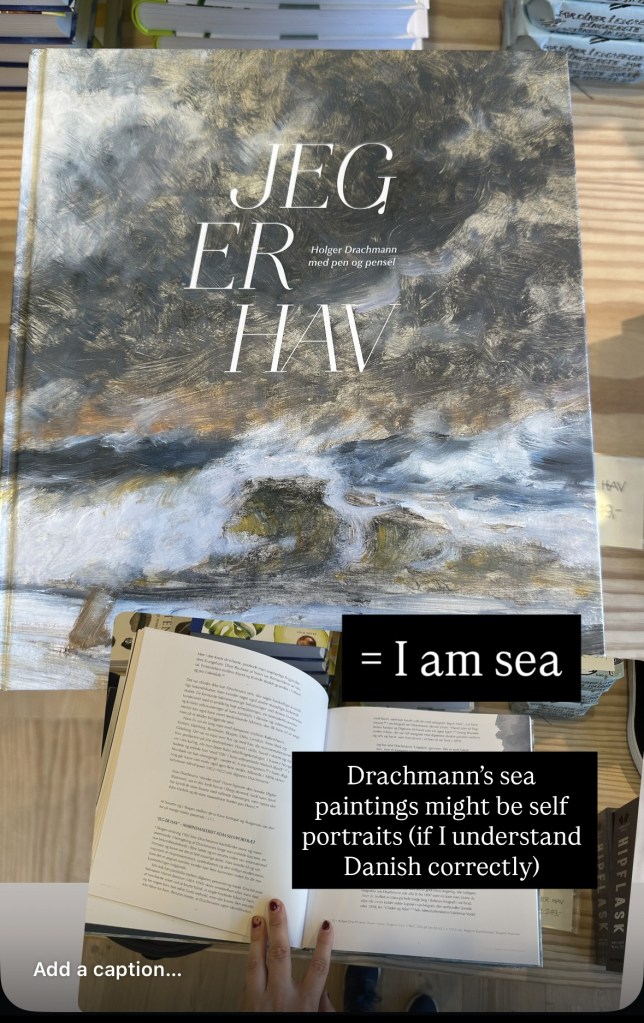

I also learned about Holger Drachman, poet and painter, who wrote that he is the sea (‘jeg er hav’). That statements sounds like the statement of a hydrosexual man. Were his paintings of the sea self-portraits?

Alone in skagen, a self-portrait during the blue hour

At first, I didn’t like Skagen very much. I arrived in the heat of the afternoon, and my highly sensitive side struggled with the noise of the busy streets filled with restaurants. But over the next two days, as I explored the beaches on my own—especially during the golden and blue hours—I was captivated by the landscape. I also experienced some magical encounters, moments of serendipity that felt almost unreal.

My Skagen story retold as a mythic, poetic travelogue — weaving my more than human world encounters with the gods I invoked

I began in the Skagen Museum, standing before Krøyer’s painting, when a French couple disturbed the silence. They apologized, explaining they had just become grandparents to a child named Leon. A name of lions, a child of sun. Their joy lingered in the air like a blessing. It was a foretelling.

Soon after, I stumbled upon a book about roses, centered on Krøyer’s Skagen painting, in the museum’s shop. There I read they were sacred to Aphrodite, goddess of love. Legend has it that Aphrodite, and is the very bloom she holds at the moment of her birth, emerging from the sea foam. From the museum’s quiet halls I walked into the heath, where wild roses and rosehips grew thorny and fragrant, as though the goddess herself was guiding my path.

Through the dunes, I reached the Baltic Sea for the first time. I lifted my camera to capture its light, and just then a message reached me: two friends I had introduced—two souls I had nudged together, like a mischievous Cupid some years ago in Japan—had given birth to a daughter. A child born at the very moment I arrived in Skagen.

I stood before the sea, perhaps before Aphrodite, the goddess who rose from its foam. I laughed at the coincidence, for weeks earlier I had declared that my Aphrodite energy had awakened, stirring the seas of my own creativity for the new ecofiction I was writing—about the ocean, about seduction, about her.

But Aphrodite does not walk alone; the wilderness belongs to Artemis. As I moved deeper into the heath, I sensed the presence of snakes in the grasses before I saw them. And indeed, two hours later, I almost stepped on a baby viper, an emissary of the chthonic powers, a whisper of Apollo, Asclepius, and Hecate. I googled ‘snakes in Skagen’ (in Danish) and found an article about a man who found a viper on his beach towel here. This sounds like a scene from the Eglė mythology.

That evening, as the golden light dissolved into the blue hour, I saw children bend to rescue a frog from the path—an innocent gesture of care, life spared in twilight. I was a bit worried about the frog. Will she not be eaten by vipers?

The next day, in the sands, as I listened to Taylor Swift’s album Folklore drifting like a spell in my ears, the earth reminded me of its sharpness: sandgrass pricked my skin. Yet just then, a yellow ladybug landed on me—tiny Tyche, goddess of chance, herald of luck. Or a herald from Aphrodite? Or the Germanic goddess Freija?

And in the evening, once again as golden light bled into blue, I encountered a deer. It stood still, sacred to Artemis, protector of the wild. I felt I had been walking not just through Skagen, but through a procession of gods—Aphrodite, Artemis, Tyche—each leaving their sign upon my path.

Wait, there are seals in skagen? About shapeshifters, skin and sexual domination

The North Sea and their stories are running through my veins, so when I see seals, I think about selkies, shapeshifters who require their seal skin to effect its magical metamorphosis. Heddle (2016) wrote an article called Selkies, Sex, and the Supernatural where she also explains that “the most common use of this motif is in tales where a man steals the skin and forces the shape-shifter, trapped in human form, to become his bride. She must remain with him, usually most sorrowfully, until she discovers where he has hidden the article, and she can flee. The fate of the female selkies mirrors that of the women of the culture which has created them. They leave their own environment of the sea to live in an alien setting under the control and sexual domination of a husband. Only when she finds her own form again can the female selkie be free. In this they are unusual as otherworld females tend to be more of the deceptive and sexually predatory kind rather than the gentle victims the selkie women would appear to be.”

Of course, I kept my senses—my tentacles—alert for spotting selkies, I mean seals, not to steal their skins and use them myself to transform into a seal, dive into the sea, and never return. I’m not even sure if it works that way. And yet, I wonder: why does this thought arise at all? Perhaps because, deep in my body, something remembers that I may have lost my own selkie skin, and I have almost forgotten it. Perhaps I long to transform into something mystical, like a selkie, because I struggle to accept my own body.

My earliest memory is of drowning—in a swimming pool near the North Sea. That trauma left me anxious during swimming lessons in primary school, a fear I had to summon great courage to overcome. The irony is not lost on me: a survivor of drowning now wants to create a hydrofeminist retelling of Eglė.

I also wonder whether Eglė ever met seals or selkies before or during her time in the Baltic Sea. Do the seals belong to the North Sea, to the Baltic Sea, or to both—even if people insist these are separate seas, divided by their levels of saltiness and brackishness?

At the place where the North Sea and the Baltic Sea meet—merging, yet never fully becoming one—I noticed a difference. The North Sea seemed wilder, its waves crowned with foam, while the Baltic lay calmer, at least during the day. But when I looked upon the Baltic at blue hour, I felt its waves grow restless. Was it the unseen presence of the moon stirring its waters?

I did not encounter any seals. Yet something within me offered consolation: the thought that if I were ever to meet them, they would recognize me and carry me back to the sea—but that moment has not yet come.

Mirror mirror, never feeling (beautiful) enough in this disenchanted world

Since childhood, I have struggled with my body image. I was never as skinny as most of my friends or the women I saw in magazines and movies. Over the past few years, I’ve come to realize the irony: I may have what could be called a “cortisol body,” shaped by years of hard work and constant stress—all in service to the same society that pressures us to look skinny and stay forever young.

My low self-esteem has often led to self-sabotage in the early stages of romantic relationships. In fairy tales, the prince comes to save you, but perhaps the real work lies in saving myself—unraveling who I am, transforming the effects of cortisol into something new. This transformation demands a different kind of work and a willingness to sacrifice convenience and luxury.

Next month marks the end of a four-year journey—perhaps even longer—lived under the weight of constant stress and anxiety. This time, however, I step into the next chapter with enough financial stability to rethink, destress, and re-enchant my life. Perhaps writing a hydrofeminist retelling of Eglė is itself part of this magical unraveling. This also means facing my body image head-on, and maybe, just maybe, some instructions for this transformation lie hidden in the concept of the hydrosexual.

I asked ChatGPT for some hydrosexual versions of the famous fairytale line “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?” I got these suggestions:

“Waters, waters, deep and wide,

whose currents flow with beauty’s tide?”

“Waters, waters, soft and clear,

whose touch is sweetest, drawing near?”

Let’s write a short, poetic fragment weaving together Eglė’s struggle with body image, her oscillation between love and death, and the snake’s gentle hydrosexual call. Before I share mine, I invite you to close your eyes and write a short passage about Eglė‘s hydrosexual descend.

retelling, fragment: The moments before entering the water again, this time to descend into the depths and meet her soon-to-be-husband

Eglė stood at the edge of the water, her reflection breaking into trembling shards with every wave. She touched her stomach, her thighs, the places where shame had taken root, whispering the cruel words she had absorbed from mirrors and gazes. The wind bit her skin, and for a moment she panicked—what if the sea swallowed her whole, what if this was not rebirth but annihilation? Pain and love twined around her like two serpents, impossible to untangle. Then, from beneath the surface, a voice rose—smooth, like the ripple of currents over stones:

“Waters, waters, soft and clear,

whose touch is sweetest, drawing near?”

The water lapped against her ankles, an invitation. Eglė stepped forward, heart pounding, unsure whether she was moving toward love or toward death, or whether the two were the same. As the tide embraced her, she felt the serpent’s body coil around hers, not to trap, but to hold. The scales shimmered like sunlight on waves.

“Do you fear me?” it whispered.

“Yes,” she breathed.

“And do you desire me?”

Her answer dissolved into the water as the snake drew her under, not drowning her, but unraveling her—pain melting into pleasure, shame dissolving into the softest touch. The sea cradled her like a womb. Somewhere in the deep, she understood: to love this way was to die a little, and to be born again.

References

- Åsberg, Cecilia. “Ecologies and technologies of feminist posthumanities.” Women’s Studies 50.8 (2021): 857-862.

- Federici, S. (2018). Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons. pm Press.

- Heddle, Donna (2016). Selkies, Sex, and the Supernatural https://www.thebottleimp.org.uk/2016/12/selkies-sex-and-the-supernatural/

- Jarosz, Ewelina. “Exploring ‘Ecosexuality’ as a manual for transdisciplinary art & research practices and a creative concept for more-than-human humanities. A book review essay of Annie Sprinke, Beth Stephens with (…).” Przegląd Kulturoznawczy 59.1 (2024): 246-265.

- Jarosz, Ewelina. “Loving the Brine Shrimp: Exploring Queer Feminist Blue Posthumanities to Reimagine the ‘America’s Dead Sea’.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 38.1 (2025): 1.

- Neimanis, Astrida. Bodies of water: Posthuman feminist phenomenology. Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- Sprinkle, Annie, and Beth Stephens. “Ecosexuality: The story of our love with the Earth.” Ecopoiesis: eco-human theory and practice 2.1 (2021): 42-48.

- Wuyts, Wendy. “Finding Satoyama–Forest bathing as a creative practice of knowledge creation and healing in/with/through damaged landscapes.” Journal of Ecohumanism 3.2 (2024): 105-133.

Instagram page: https://www.instagram.com/flowing_with_egle/

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.