Zürich is a city of deep, layered histories. As you walk down toward the Fraumünster church, you pass through Thermengasse, where remnants of a Roman thermal bath lie beneath your feet. There you’ll find traces of the Roman bathhouse and a plaque describing its Celtic origins. The Lindenhof, a peaceful hilltop park today, was once the Roman heart of Zürich—then called Turicum. Long before all of this, most of what is now Zürich was forest.

It’s strange to remember that cities were once forests—both literally and figuratively.

To be honest, I’ve never been in love with Swiss towns—only with Swiss men. I don’t know why cities like Zürich, Basel, or Bern don’t immediately come to mind when people ask me where I’d like to stay for a long time. I just don’t see the magic.

It’s been ten years since I last visited Switzerland. That trip was for a project in Lausanne, and I added two days in Zürich. It happened to coincide with Sechseläuten, the spring festival in Zürich where members of historical guilds parade in costume to celebrate the end of winter. Both Lausanne and Zürich surprised me in their own quiet, unexpected ways.

During my two free days in Zürich, I was seeking traces of the ancient, mystical forest that once surrounded Zürich—and its connection to Artemis. This blog post explores how my current project on rewilding local saints helped me experience Zürich in a new, enchanted light.

Zürich: The Most Capitalist City in Europe?

At one point during my visit, we stepped inside an old building—once a bank, possibly still a bank. It felt like a “cathedral of capitalism,” as the guide put it. A recent nonfiction bestseller, The Meltdown, chronicles the corruption and arrogance that led to the downfall of Credit Suisse. You cannot unsee the clocks and banks in Zürich—symbols of control over time, money, and what are so often called “resources.”

But as I walked, I was also struck by the lush greenery. I skipped the old city center and looked instead for a bar with a library. It was unseasonably hot—uncomfortably so. While others might call it lucky to experience Switzerland in full sun, my northern body couldn’t help but feel the weight of climate change. I am a cold-weather person. No, this heat is not normal.

Then, the fountains. Zürich is a city of fountains. Cool, shaded, drinkable—free water in stone basins. Something about them felt ancient, pagan even. I thought of Celtic stories about sacred wells, healing waters, and female spirits tied to nature.

Fraumünster and the Woman in the Name

Frau means “woman.” In the 9th century, the abbey of Fraumünster was founded. It once held immense power. The abbess even had the authority to approve Zürich’s mayors.

The deer—symbol of Artemis—kept appearing in my thoughts and surroundings. Was this coincidence, or a code?

Recently I came across texts about Marian devotions linked to wells, rocks, and linden trees (see Sacred trees, Mystic Caves and Holy Wells in rural Spain – or to-visit-sites in your next Spain trip). Zürich still carries echoes of that forested past: old trees, hidden wells, timber benches crafted from what looked like ancient trunks. Where had they come from? What stories do they hold?

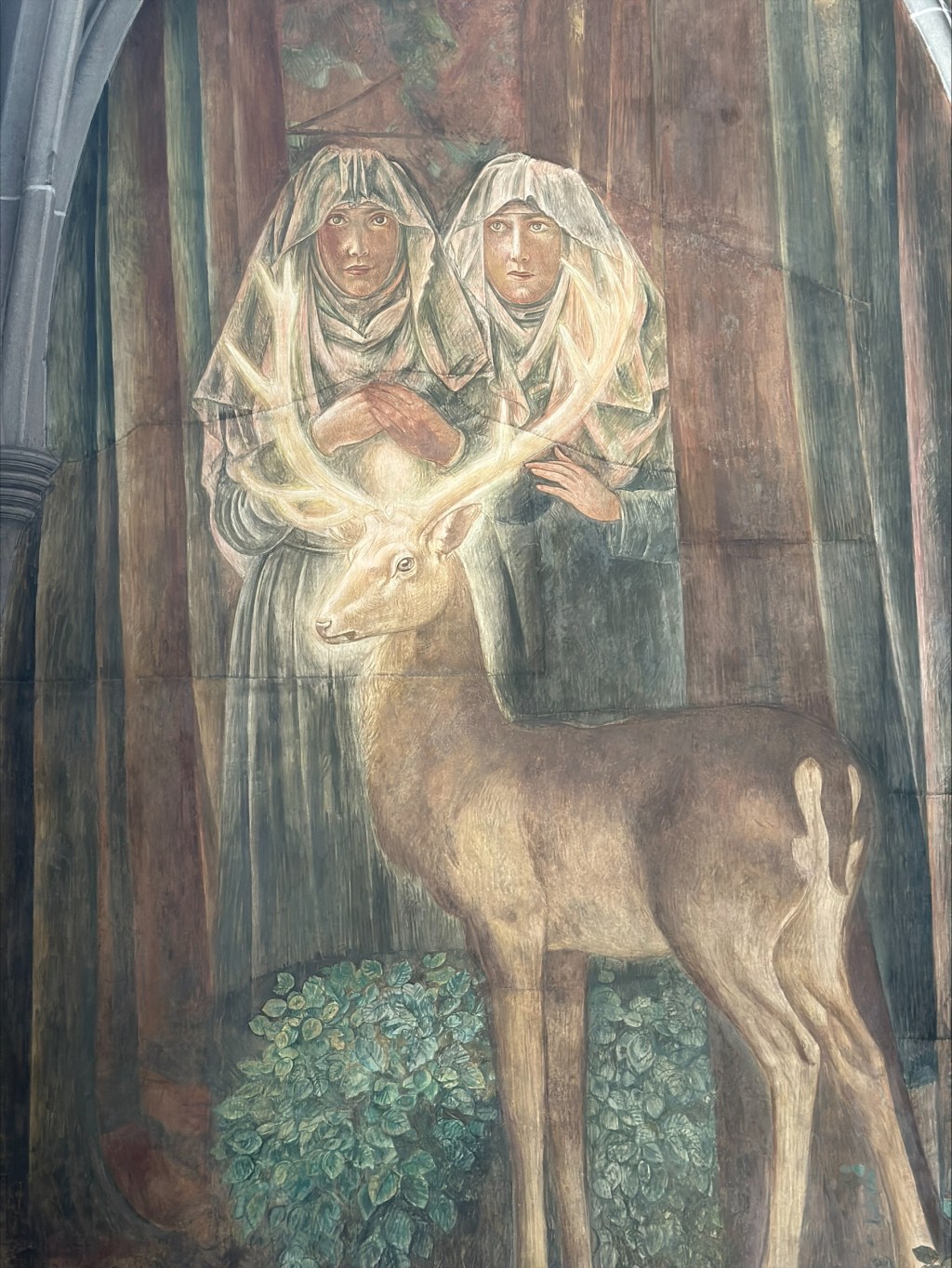

Artemis. Yes, I could feel her presence. In one small alley, I sat in the shade in front of a mural. Tourists passed by, often Spanish-speaking guides explaining the sites. I let myself pause. According to legend, two sisters, Hildegard and Bertha, daughters of a nobleman, lived in a fortress high in the mountains above Zürich. Each evening, a deer with glowing antlers would appear and guide them safely through the dark forest, down to the banks of the River Limmat. There, at the water’s edge, the sisters would pause to pray, before the mysterious stag led them back home through the woods. Interpreting this as a divine sign, the sisters believed that a religious foundation should be established on that very spot. Their father eventually agreed, and a monastery for aristocratic women was founded, with Hildegard becoming its first abbess.

While this legend was later Christianized, it may preserve traces of a far older, pre-Christian tradition. The image of a glowing-horned deer guiding maidens through the forest evokes strong associations with Artemis, the Greek goddess of the hunt, protector of young women, and guardian of wild animals and sacred groves. Forest worship dedicated to Artemis—or a local goddess of similar attributes—may well have taken place at this location long before the abbey was built. The enduring motif of the deer as a divine messenger could be a cultural echo of such ancient rites, subtly preserved through legend.

Linden Trees and Forgotten Stories

Passing through Lindenhof and other remnants of Roman and pagan times, I felt the layers of the city: snowmen in spring, May Day rituals, liquids made from linden blossom.

One guide introduced me to Bircher muesli, and to Daniela—the cheese goddess, as she called one of the local cheese vendors. The guide said that the doctor who introduced Bircher muesli had probably the recipe from a local woman from the rural areas. Where have I heard this type of story before? The guide told a haunting story of a woman who gave a child a cookie. When the child later died, the woman was accused of witchcraft and executed.

It all tied back to a loss of power.

The abbey once had political sway. By the 14th century, the guilds had taken over. Then came the witch hunts. Women burned. Centuries later, Switzerland was still denying women the right to vote until the 1970s.

On Privilege and Re-Enchanting Life

I know I’m privileged. A few years ago, I sold a piece of land—a legacy from my grandmother’s side of the family. Her aunts had been sent to a convent in exchange for land for her grandfather. That sale gave me – three generations later- access to education, networks, and the ability to add personal days in expensive countries like Switzerland while traveling for work.

I’m often invited to speak or write. I create these blog posts in my free time. But I always try to remember the women who came before me—those who paved the way, and those whose paths were erased or set on fire. We’re not always their daughters, but we should still honor them.

Wherever you go, try to notice the forgotten stories—of forests, of wells, of women who once were the source of building, not construction but community. Ask where a recipe came from. Was it really one “genius” chef or doctor? Or a village of women and men, in kitchens and fields long gone?

Ask about the women. Even the mythical ones.

Find a quiet moment of peace in this world of endless apocalypses. Especially those of us who are women—especially women of color or others whose voices have been long silenced—we know how easily rights can be lost.

In Zürich, I walked the ghostly outlines of an ancient forest where Artemis was once honored. I sat in an abbey where women once chose mayors. And while numbing myself with pasta and applesauce in a former guild hall, I was reminded: even when we gain rights and power, they can be taken away. Quickly.

Do you want to learn more?

Sign up to a newsletter to receive blogposts and/or online workshops about Rewilding (female) saints. As you can see, a blogpost is written once a year, so this will be a very slow newsletter.

You can sign up via this link or by scanning this QR code:

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.