Today, I facilitated another Writing(with)Plants session, this time inviting the presence of the birch tree. During the creative writing segment, I found myself exploring who Birch might have been before transforming into a tree, inspired by the Baltic myth woven into our Flowing with Eglė – Project. The narrative deepened as new elements emerged, carried in by the spirit of the season: carnival, tricksters, labyrinths, mazes, holy fools, and laughter.

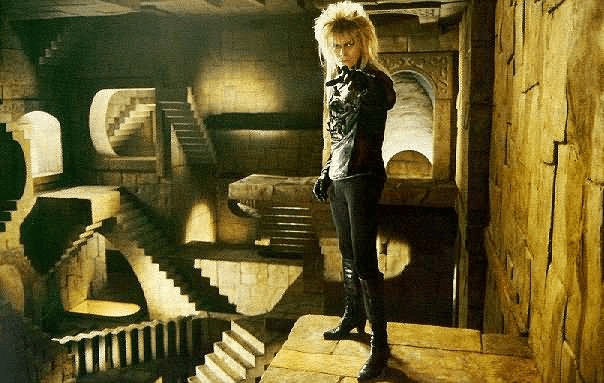

It felt only natural to begin the session with a song by David Bowie—As the World Falls Down—from the 1986 film Labyrinth. The haunting melody and masked dance scene perfectly capture the essence of tricksters and the whimsical, topsy-turvy world of carnival. Truly, what other song and video could better embody the spirit of trickster times and playful folly?

Birch is not the trickster, but her story is about finding love with a fool

While preparing for the session, I found myself reflecting on what Birch’s story might be within the myth. In Lithuania, birch is often seen as a symbol of purity and goodness—commonly associated with a good, innocent boy who embodies virtue and healing. As a tree, Birch is known for its restorative properties and its role as a pioneer thriving in open spaces under the sun. Yet, despite this traditional imagery, I struggled to picture Birch as a boy. To me, Birch resonates with a distinctly feminine energy, as I explored in my earlier blog post, Flowing with Eglė meets Writing(with)Birch.

This led me to imagine Birch as a transwoman. In the narrative where Eglė and her four children—including Birch—return to the patriarchal world on land, I envisioned Birch cleverly disguising herself as the “good boy” society expected, skillfully tricking everyone. Isn’t this theme of concealing one’s true identity to fit societal norms timeless?

During the session, one participant from the USA reflected on how certain words—like “gender”—have become almost taboo in today’s cultural landscape. It made me wonder: perhaps this is exactly why we need the energy of the trickster and the use of masks—to navigate societal expectations while staying true to who we are.

The relationship with the dad

While watching David Bowie as the Goblin King in Labyrinth, it struck me—he could just as easily play the role of a Snake King. His enigmatic presence, his playful yet sinister charm… it fits perfectly with the serpentine, trickster archetype. This realization lingered as we continued the session, and I couldn’t help but bring up an interesting thought: perhaps we shouldn’t forget that Birch is not only the child of Eglė but also the offspring of an immortal, snake-like trickster. This raises the question—what was his/her/their relationship with their father truly like?

Was Birch shaped by the cunning, transformative nature of the Snake King? Did this influence Birch’s ability to mask their true identity or to navigate societal expectations? It’s a compelling layer to the story, especially when considering Birch as a transwoman who might have needed to conceal her identity to fit into a patriarchal world.

And yes… as the old saying goes, maybe the daughter did fall for someone who reminded her of her father. It makes you wonder—did Birch inherit more than just the Snake King’s trickster spirit?

The symbiotic relationwhip with Fly agaric

During the writing(with)plants session, a memory surfaced—a birch tree from my childhood, standing proudly on my parents’ street, with a mushroom nestled at its base. Even as a child, I was aware of the symbiotic bond between them. By a twist of fate, I happened to be at my parents’ home when I facilitated this Writing(with)Plants session, and that memory seamlessly wove itself into my creative writing, bringing Birch and the mushroom together once more.

This particular mushroom isn’t exclusive to birch trees; it forms relationships with beech, oak, pine, lime, and spruce as well. It reminded me of a blog post I wrote a few years ago—Norway Spruce: A Story About Shaman Claus, Mushrooms, and Fire—where I delved into the connection between the spruce and this mystical mushroom. Curious to deepen this narrative, I looked up its Lithuanian name: Paprastoji Musmirė, or Papras for short.

From there, a character began to take shape in my mind—a trickster living in the patriarchal kingdom ruled by Birch’s twelve uncles. Papras is the son of a shaman healer, gifted with the ability to see the truth yet known as a jester, a holy fool who wears countless masks. During carnival—or perhaps another spring festival—he encounters Birch and is instantly captivated. Birch feels the spark too, but remains uncertain. Can Papras truly see her for who she is beneath all her masks? Or is it just another trick of the fool?

This unfolding story felt timeless, echoing the themes of identity, disguise, and love—perfectly fitting the season of tricksters and transformation.

in the labyrinth, death does not exist

The story of Birch, her mother, and her siblings culminates in a profound transformation—they all become trees after her father is killed by her uncles. It could easily be read as a tragedy, a tale of loss and defeat. But within our Flowing with Eglė – Project, we are reimagining this myth. We’re careful not to let it become just another story of patriarchy triumphing over chaos, monsters, and women. Instead, we are planting hopeful seeds, seeking endings that carry the promise of new beginnings.

Birch’s transformation into a tree might seem to sever any possibility of human connection—unless Papras, the trickster-jester, undergoes a transformation of his own. If he becomes the mushroom, then they can continue their relationship in a different form. As nonhuman beings, they can exist in a symbiotic relationship, intertwined at the roots, sharing pain, grief, and maybe even joy. Together, they defy the constraints of a patriarchal world by embracing their true selves through metamorphosis.

Strangely enough—though by now, I’ve come to expect these “coincidences”—another project member shared a quote just as I was deciding to weave David Bowie’s Labyrinth into the session:

“Whereas in a maze you have to make choices about which path to take, and can thus get lost in cul-de-sacs, in a labyrinth you are guided by the path, A labyrinth is not a puzzle to be solved but a journey to be experienced. There are no wrong turns, no dead ends—only ongoing comings, goings, and meanderings. This insight resonates deeply with the story we are crafting. Even death is not an end but a creative transformation—a turn in the ceaseless unfolding of life itself.” — Sevenhuijsen, Labyrinths of Care (2003).

In this labyrinthine journey, Birch and Papras are not lost. They are simply continuing their story in a new form, guided by the path, navigating a world that cannot contain them in human shapes.

Labyrinth, path of the holy fool?

In my wandering through the world wide web (not the wood wide web—though, sometimes, they feel the same), I stumbled upon a book title that linked the labyrinth to the path of the holy fool. It immediately reminded me of Baubo, one of my favorite goddesses from Greek mythology, and Uzume from Japanese mythology. Both figures are sacred tricksters and divine fools, embodying laughter and irreverence as pathways to healing.

Baubo, in the Greek myth of Persephone and Demeter, is the holy fool who breaks through Demeter’s overwhelming grief with bawdy humor and laughter. After losing her daughter Persephone to the underworld, Demeter is inconsolable, her sorrow so deep that it causes the earth to wither. It’s only when Baubo performs her shameless dance, lifting her skirt and making Demeter laugh, that the goddess begins to heal, allowing life to bloom once more.

Uzume, similarly, uses humor and dance to coax Amaterasu, the sun goddess, out of her cave of mourning, restoring light to the world. In both myths, laughter is the medicine that heals grief—a sacred act that bridges despair and hope. (see Changing the Stories We Live By #4: Grief.)

So, why is there no holy fool in the story of Eglė and her four children?

Where is the figure who can break through the sorrow, who can transform pain into laughter, even amidst tragedy? The myth is steeped in loss and transformation—Eglė loses her husband, her children are turned into trees, and she herself is transformed, rooted in grief.

But what if we reimagine the story? What if we weave in the presence of a holy fool—a Baubo or a Uzume—who brings laughter as a form of healing? Could Papras, the trickster-jester who falls for Birch, play this role? Could he use humor to bridge the gap between worlds, to soften the harshness of loss, to transform the labyrinth of grief into a path of healing?

SCENE seTTING: cARNIVAL

The retelling of Birch’s story unfolds during Carnival—not just because we’re celebrating it now, but because spring is the heartbeat of the Eglė myth. It’s the season when life awakens, and in the tale, it’s the cuckoo who leads Eglė, Birch’s mother, to the Snake King, setting in motion the cycle of love, loss, and transformation.

Carnival, in this context, isn’t merely a celebration. Its roots run deep, tracing back to ancient European festivals like the Greek Anthesteria and the Roman Saturnalia. During these festivities, social hierarchies crumbled, rules were suspended, and the world turned upside down. It was a time of chaos, laughter, and liberation—a brief moment when the established order gave way to debauchery and jest, only to be renewed once the carnival season ended.

From an anthropological perspective, Carnival is a ritual of reversal. Social roles are flipped, masks conceal identities, and norms around acceptable behavior are joyfully cast aside. It is a time of metamorphosis, of shedding old skins, of embracing chaos to pave the way for rebirth.

Historically, winter was seen as the domain of winter spirits—cold, dark, and unyielding. Carnival marked the ritual expulsion of these spirits to summon the return of summer, light, and fertility. It was the first spring festival of the new year, celebrated by Germanic tribes as a rite of passage from darkness to light.

In the retelling, Carnival becomes more than just a backdrop; it is a catalyst for transformation. It is the perfect setting for Birch and Papras to confront their identities, to wear masks and shed them, to navigate the labyrinth of self-discovery. It is during this chaotic celebration—where nothing is as it seems—that Birch, born from Eglė and the immortal Snake King, finds herself drawn to Papras, the holy fool who embodies truth and trickery.

Amidst the revelry, Papras dances between identities, between masks and faces, just as Birch wrestles with her own transformation. They are both creatures of liminality, existing on the borders of human and nonhuman, of male and female, of order and chaos.

In the labyrinthine chaos of Carnival, perhaps they can finally see each other for who they truly are—beyond the masks, beyond the roles dictated by a patriarchal world. Perhaps, in this sacred dance of reversal and renewal, Birch and Papras can rewrite their story.

The retelling, fragment 8

The moon hung low and full, its silver light spilling over the clearing where the celebration was in full swing. Lanterns swung from branches, their flickering light casting dancing shadows on masked faces. Birch stood near the edge, her slender form half-hidden behind a column of amber. She could feel the rough bark pressing against her back, grounding her as her eyes followed Papras through the crowd.

He moved like smoke, slipping in and out of swarms of guests, his laughter curling through the air like incense. Papras wore the mask of a jester—a wide, painted grin stretching across his face, its eyes exaggerated and gleefully wicked.

Her eldest uncle’s voice boomed through the clearing, his commanding presence reminding everyone who ruled here. Twelve uncles, twelve patriarchs, each one more imposing than the last. But tonight, they wore masks too. However, everyone could recognize them. Their voices were too loud. They would not let power slip away, not even at this evening.

Nobody had recognised her. She was wearing a white dress and jewelry that her father had gifted her. Her father had not wanted her to bring it with her to the land. Her father knew that her uncles and all the other people saw her as a boy, a nice pure boy, too nice to be bullied, but looking too pure to not be teased. One of her uncles had teased her that she looks more beautiful than his daughters. ‘I never met a guy who washed his hair that often.’ Birch’ mother, Egle, had silenced her brother by observing loudly that he was jealous. ‘Just ask what he uses to wash his hair, my dear brother, and you might attract as half as many girls as him.’ Birch heard whispers that she was as beautiful and godly as these mysterious viking raiders, who also washed their hair so often – according to the stories of the traders and merchants in town. ‘Is his father a viking?’ Many questions traveled through the houses and streets that Birch visited with her mother and siblings in the past days. Birch became even more conscious about her identity, her roots, and she became even more confused.

“Is the good boy too shy to dance?” Papras’ voice was suddenly at her ear, close enough that she could feel the warmth of his breath. Startled, Birch turned, her cheeks flushing even before she met his gaze.

“Don’t call me that,” she hissed. “They cannot know who I am.”

Papras tilted his head, the painted grin of his mask making his teasing even more infuriating. “Oh, I know,” he purred, his voice low and smooth.

“How?”

“No lady here has your beautiful hair.”

Birch’s breath caught, her heart pounding as his words seemed to wrap around her like vines, tightening.

“But tonight, nobody cares.”

She crossed her arms. “Do you care?”

He hesitated. “I know that you are a woman, Birch, that you have been wearing a mask of a good pure boy, but I can see through it” he whispered, his voice dropping to a tone that made heat rise along her neck, her skin tingling.

“How do you know?”

“You are not so original with your questions.”

“What do you want from me?”

“I want to dance with you.”

“No, you’re too wicked,” she managed, though her voice was shaking.

“Are you waiting for someone else?”

“Of course I am.”

He leaned in, so close that his mask almost touched hers. “Does he know who you really are?”

She wanted to shove him away, but her hands refused to move. “You’re impossible.”

“I’m inevitable,” he said. “You and I, Birch… we’re made of the same chaos. I just hide it better.”

His fingers brushed hers. Birch shivered, her body betraying her even as she tried to maintain her composure. “Someone will see us.”

“They’re too busy pretending they don’t have masks under their masks,” Papras said, his eyes flicking to her uncle, who was laughing a little too loud, his shoulders a little too tense. “You and me, Birch—we’re the only ones truly free tonight. Just two creatures playing pretend.”

His words were a spell, a lure that she found herself helplessly drawn to. Birch felt her roots shift, her branches sway, her heart thudding like the drums echoing through the clearing. For a moment, she saw them as they truly were—tree and mushroom, entwined beneath the earth, a tangle of roots that no one could separate.

TO BE CONTINUED.

Read more about the project and find other blogs here: Flowing with Eglė – Project.

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.