In the past weeks, I have been listening to Sylvia Linsteadt‘s recordings, via the advaya platform ‘ When Women Were the land‘. In her first chapter, she focuses on the Motherhouse and the theories of the Lithuanian archeomythologist Marija Gimbutas.

As I work with other European myths, in my Flowing with Eglė – Project and Re(Wild)ing Sarka project, I challenged myself on a weekend to apply Linsteadt’s introduction into the concept of the motherhouse and Gimbutas’ theories on the myth around Libuše, Šárka and Přemysl.

The traces are there. Of course, this blog is part of clicking many wikipedia pages, reading anthropological theories, and my own musings about mythology in the past ten years.

A dictionary

- Archeomythology is an interdisciplinary field that merges the study of archaeology with mythology. Developed by the Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, this approach integrates her extensive knowledge of European folklore, linguistics, and her intuitive understanding of cultural artifacts. Gimbutas applied these insights to explore ancient cultures, particularly those pre-dating Indo-European influences.

- Old Europe is a term coined by Marija Gimbutas to describe a relatively homogeneous pre-Indo-European Neolithic culture centered in the Lower Danube Valley of Southeast Europe. This culture, according to Gimbutas, exhibited traces of matrilocal living arrangements, suggesting a societal structure where women’s roles were central.

- Matrilocal refers to a societal system in which a married couple resides with or near the wife’s parents, thus emphasizing the woman’s side of the family.

- Matrilineal is a term used to describe a form of social organization in which lineage, or ancestry, is traced through the mother’s line. In matrilineal societies, property and family name are inherited through the female line.

- Matriarchal describes a social system where females, particularly mothers, hold the primary power positions in roles of political leadership, moral authority, social privilege, and control of property. Although often discussed in anthropological contexts, true matriarchal societies are rare.

Together, these concepts form a framework within which Gimbutas examined the archaeological record, seeking to uncover the roles and influences of women in early European societies.

sYLVIA’S INTRO INTO THE MYTH OF EUROPE AND ZEUS

In the first chapter of her advaya course, Sylvia mentioned the myth of Europa and Zeus, a tale from Greek mythology where Zeus, the king of the gods, disguises himself as a magnificent white bull to abduct Europa, a Phoenician princess. Lured by the bull’s cute appearance, Europa climbs onto its back, whereupon Zeus carries her away across the sea to Crete. There, Europa becomes the queen and eponym of Europe, signifying a narrative of conquest and transformation.

This myth can be connected to archeomythology, particularly in the work of Marija Gimbutas, as it embodies the thematic elements of cultural assimilation and transformation that are prevalent in her studies. Sylvia made more interesting links, but I recommend to follow the course to get more fascinating details and traces.

the collective memory of the loss of women’s rights since 3500 BC

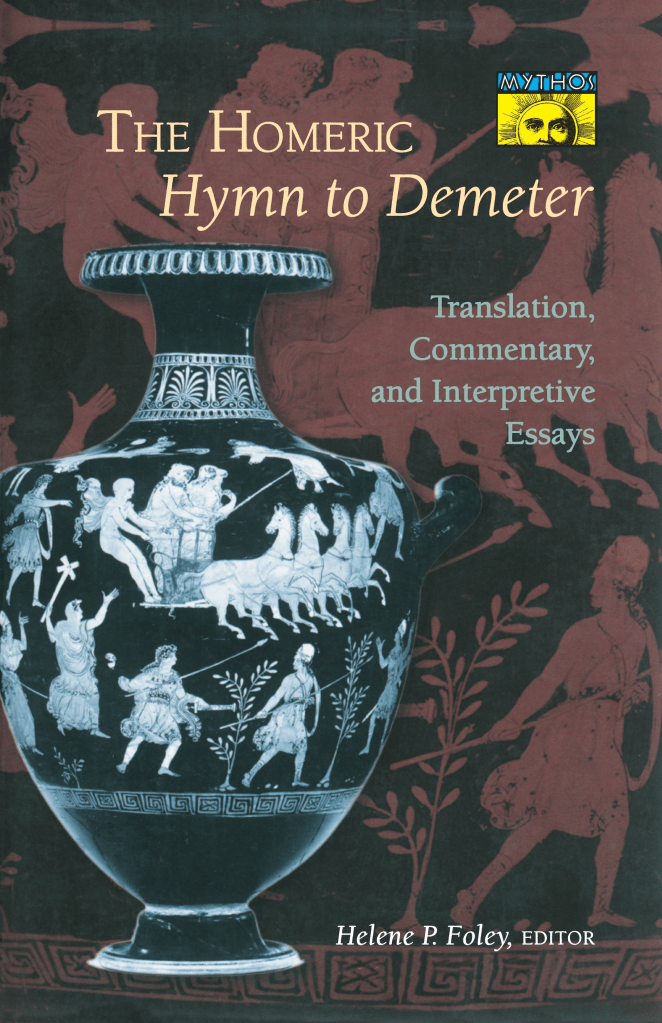

While listening to her advaya course ‘When Women Were the land‘, Sylvia reminded me also to the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, which captures the symbolic erosion of women’s rights and the shifting dynamics from matrilineal or matrilocal cultures to patriarchal dominance that began around 3500 BC. In this myth, Zeus orchestrates the abduction of his daughter Persephone, negotiating her fate with Hades without the knowledge or consent of either Persephone or her mother, Demeter.

This act of betrayal not only highlights Zeus’s authority over his female kin but also reflects a broader societal shift where the rights and autonomy of women were subordinated to male control. The narrative mirrors historical transitions in ancient societies where matrilineal customs gave way to patriarchal structures, significantly altering the social and familial roles of women. This myth, thus, serves as a cultural memory of the gradual but profound loss of women’s rights, echoing the deep-seated historical shifts from female-centered to male-dominated societies.

My link with prague

In 2013-2014, I lived in Prague and experimented with videography. I was always looking for a story. In this period I learned about the legend of Libuše, Přemysl, Vlasta and Sarka. I loved and I hated the story…

Why do I hate it? The legend of Libuše, the prophetic founder and ruler of Prague, casts a long shadow over the historical narrative of Bohemia, especially highlighting the period following her death known as the Maiden Wars.

Why do I like it? The story revealed that there might have been some sort of matrilocal culture in the land where I was rooting. See also a previous blog: Rewilding the Czech legend of Libuše’s vision and Wild Sarka,.

The oldest venus figure in the world

And I found more traces of this matrilocal society. The legend is maybe not based on the Amazons, but maybe has a deeper rot. When I was surfing in the internet, looking for more traces, I discovered that the oldest Venus figure in the world, dating back to 29,000 BC, is found in Czech Republic, the home of Šárka, Vlasta and the other Maiden Warriors.

tHE Bohemian MAIDEN WARS – the last stand against patriarchy ?

The Maiden Wars erupted in response to the ascendancy of Přemysl, Libuše’s’s husband who inherited the throne and shifted the societal balance dramatically away from the egalitarian principles that had empowered women. Under Přemysl’s rule, the women who had once enjoyed equal status and rights found themselves marginalized, sparking a fierce resistance known as the Maiden Wars.

This rebellion can be interpreted as a strong symbol of the struggle against the encroaching patriarchy, marking a desperate attempt to preserve the remnants of a society that might have once been matrilineal, matrilocal, or even matriarchal.

Drawing upon Marija Gimbutas’ theories, if one were to recontextualize the legend, it might be placed as far back as 4000 BC, a time more consistent with the prehistoric cultural shifts from female-centered governance to male-dominated hierarchies.

Marija Gimbutas’ exploration of Neolithic female figures and goddesses reveals a profound reverence for feminine symbols throughout ancient Europe.

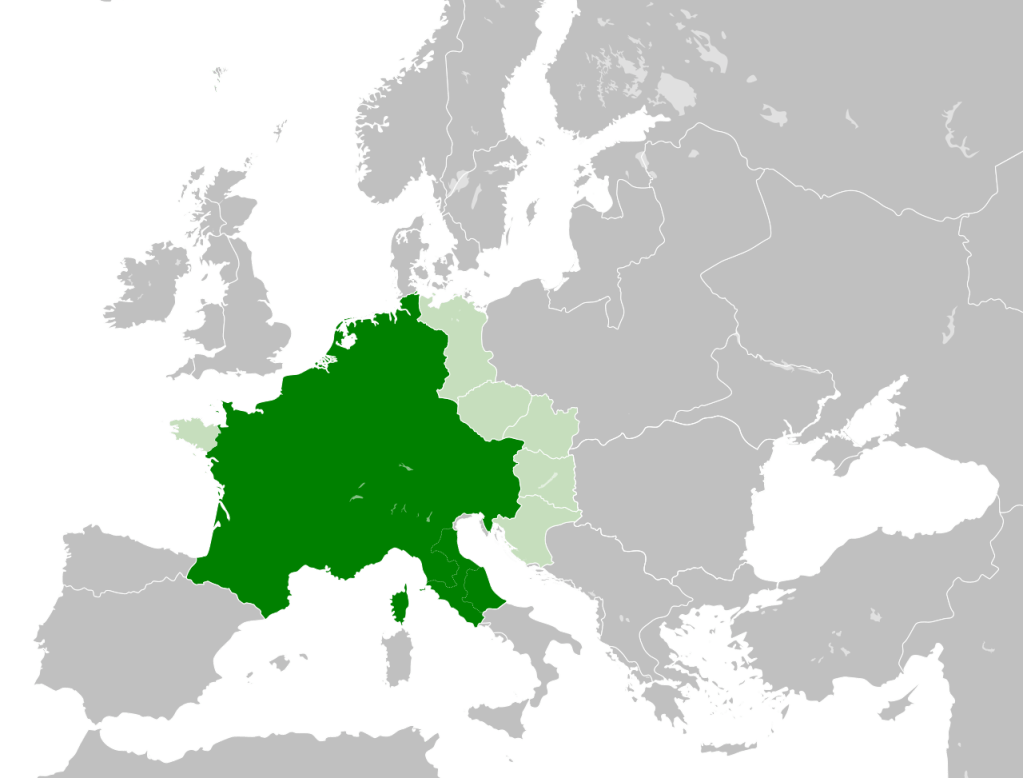

On the other hand, the carolingian empire was the first version of the holy roman empire …

Contextualizing the story of the Maiden Wars in the 8th century aligns intriguingly with the rise of the Carolingian Empire, which culminated in Charlemagne being crowned Emperor in 800 AD. This period marks a significant transformation in European political and social structures, with the Carolingian Empire acting as a precursor to the Holy Roman Empire.

During the 9th century, amidst this backdrop of burgeoning central authority, local populations, including those in the deep forests of what is now the Czech Republic, often resorted to guerrilla tactics to resist the expanding influence of imperial power. I am not the biggest expert in Czech history, but I understood that this resistance had set the stage for the emergence of the Přemysl dynasty, which would come to shape the region’s history profoundly. In addition, we all know the patriarchal nature of the Catholic Church in those ages and how they have helped in the erasure of some practices…

In the 12th CENTURY… THEY TALK ABOUT 7 mythological princes, one for each day …

Cosmas, a 12th-century chronicler and known as the first man who documented the myth of the Maiden Wars, further cemented this shift towards a patrilineal society by mythologizing the rulers of this dynasty, tying them back to legendary figures and narratives that underscored male dominance. This historical framing by Cosmas illustrates a deliberate crafting of history to emphasize patriarchal lineage.

The number seven, much like twelve, carries deep mythological significance, often used to structure narratives that justify and impose patriarchal control. This symbolism can be seen in the story of the seven mythological princes from Czech legends (the seven princes are each other’s son, starting with the son of Libuse and ending with the father of Bořivoj; but there is not really evidence that these 7 generations of men lived). If I understood some texts, each prince is representing a different day of the week, embodying the patriarchal imposition of order on what was perceived as chaotic.

… or the patriarchal process of bringing order through control

This thematic device mirrors the story from Baltic mythology mentioned in the “Flowing with Eglė – Project,” where twelve brothers confront and conquer chaos and a serpent, reinforcing the motif of male heroes subduing disorder.

These numbers (7, 12) and their associated myths, including those involving major figures like Zeus and Apollo, often serve to reinforce the narrative of male dominance and control, as seen in the abduction of Europa and the transactional betrayal in the Homeric Hymn of Demeter. Here, Zeus’s decision to hand over his daughter Persephone to Hades without the consent of her or her mother Demeter, is a stark example of patriarchal authority and manipulation.

In my work with another myth, coming from the Baltic regions, Flowing with Eglė – Project, I encountered also 12 brothers who kill the snake husband. Apollo killed the Pythia. And we all know the link between snakes, chaos, water and divine female work (see e.g. The water lily, the serpent and the nøkk, an ecofeminist trinity?).

The numbers connected with time, like 7 and 12, that frequently accompany such myths about violence against women and nonhuman nature, reflect a broader cultural and historical pattern where order is imposed through patriarchal structures. Are the seven mythological generations of princes referring to real men, or to a certain patriarchal process of bringing order through control in the 8th-12th century?

If I would do an ecofeminist retelling…

I would root the Czech myth of the Maiden War in the 8th-9th century, imagining a vibrant society where women still worship the ancient goddesses, their rituals and wisdom deeply connected to the land and seasons. This matriarchal strength, however, would be overshadowed by the looming threat of the Holy Roman Empire, a force intent on reshaping their beliefs and sovereignty.

The myth has a sad ending, but I would rewrite the myth into a historical fantasy, with ecofeminist elements (read more about my intentions in Re(Wild)ing Sarka).

In this retelling (still in dreaming, not in writing phase yet), the happy ending would arise from reintroducing figures who may have been erased over centuries or millennia, figures whose presence could restore balance and agency to the narrative.

Drawing inspiration from the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, I would weave into the tale the four mothers—archetypes who guide and empower Libuše, Šárka, Vlasta, and Přemysl—alongside a pivotal childless trickster, Baubo, the sacred jester. Baubo’s humor and irreverence, often dismissed in history, would serve as a catalyst for unity and transformation, reminding the characters of their shared humanity and the cyclical resilience of the earth itself. The daughters might have died by the end, but the mothers and their remaining daughters might continue the stories, the rituals, the memories, in hidden groves and in kitchens.

Perhaps -especially as this day invites this idea – add a bit of Brigid’s energy in the retelling. Some fire and transformation.

In which period would you recontextualize these Czech myths and why?

Discover more from Stories from the Wood Wide Web

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.